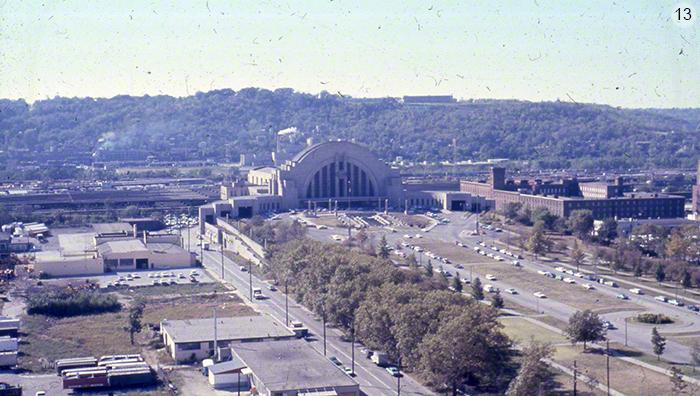

Temple to Transportation — 1933–1972

Union Terminal opened in the March of 1933, nine months ahead of schedule.

Described as a "Temple to Transportation" by the local and national press, Union Terminal was in many ways a dream come true for Cincinnati. For 50 years, various plans had been put forward for a unified rail station in Cincinnati. Finally it had arrived, and it was undoubtedly one of the finest stations ever built.

Everything you could ever need

It was nearly a city within a city. The main concourse offered shops for everything: a bookstore, toy store, men’s store, women’s clothing store, food service, newsstands and even an air-conditioned movie theater. Large lounges with large connecting restrooms were available for men and women, along with a bootblack and barber shop. There were even bathtubs available in the restrooms for passengers on long trips. Practically everything but a bed was available, and all was decorated in the stunning Art Deco style.

Managing automobile, bus and human traffic

Organizationally the building was a marvel. Incoming vehicle traffic was split into three ramps. The first ramp served taxis and cars, the second buses, and the last was for streetcars. While the streetcar line was never connected, the other two dropped passengers off on the north side ramps then proceeded under the rotunda and came up on the south side where ramps brought passengers down to the vehicles to depart. Thus all arriving and departing traffic was split between the two sides of the rotunda and wouldn’t get in each other’s way. When it opened in 1933, the Cincinnati Enquirer newspaper declared "An enormous throng can be handled in the great rotunda without annoying a single passenger." Today the north side ramps are a part of the Museum of Natural History & Science and the south side ramps are a part of the Cincinnati History Museum.

The massive 180-foot-wide and 106-foot-tall Rotunda, today the largest half-dome in the Western Hemisphere, is the primary space. When the building opened in 1933, it connected to another important space, the train concourse, a 450-foot-long structure that sat over the tracks below. Here 16 train gates connected to the platforms where passengers and baggage would be loaded or unloaded from the train. Baggage was checked by passengers in the Checking Lobby, today the area in front of the OMNIMAX® Theater, where it was then taken by elevator to the lower level for sorting. A tunnel ran out from the baggage room under the tracks and ramps lead up from this tunnel to the platforms above. This allowed baggage to be handled out of the way of passengers so that the two would not get in the way of each other.

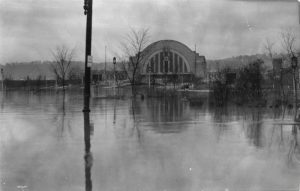

The Great Depression, the 1937 Flood and Union Terminal

The reality that Union Terminal was born into was far different than her builders had dreamed of six years before. The Depression had hit the railroads hard, and the number of people travelling by train was declining. Some wondered whether building such a massive structure had in fact been wise and some even labeled the building a white elephant. Despite a great deal of fanfare over its opening, Union Terminal was decidedly quiet during the first few years.

Higher than average rainfall along the Ohio River and its tributaries in January 1937 set the stage for Cincinnati’s highest and most disastrous flood. By January 26, the river crested at an incredible 80 feet, leaving some 45 square miles of Hamilton County underwater, and more than 61,000 of its residents without homes.

Higher than average rainfall along the Ohio River and its tributaries in January 1937 set the stage for Cincinnati’s highest and most disastrous flood. By January 26, the river crested at an incredible 80 feet, leaving some 45 square miles of Hamilton County underwater, and more than 61,000 of its residents without homes.

Efforts had been made from the very start of the terminal project to make the facility safe from Millcreek Valley flooding by raising the tracks and other facilities above the level of the highest previous recorded flood. The 1937 flood left the terminal a virtual island. Hopkins Street, Kenner Street and Freeman Avenue, as well as the entire approach to the terminal plaza, were submerged at the peak of the flood. But even at 80 feet, the terminal itself was basically high and dry. Flooding on the lower levels of the building did not affect the tracks and platforms and other passenger facilities in the building.

At the peak of the flood, Union Terminal still handled the trains of the Southern Railroad, although electricity for lights and switches had to be provided by portable generators. Three of the railroads (Pennsylvania, B&O, and New York Central) continued their operations from suburban stations during the flood, while the C&O, L&N and the Norfolk & Western eventually were forced to stop all trains. Passengers coming into the station by Southern Railroad had to be taken to the Fourth Street Station by a C&O shuttle train.

Union Terminal during World War II

Union Terminal had quickly earned a place as one of the jewels of the Queen City. Everything from post cards to advertisements used Union Terminal’s iconic architecture as a backdrop. But Union Terminal would not be relegated to the role of scenic background for advertisers. As war loomed in Europe, the United States began preparing for the possibility of war. In June 1941, the first Troops in Transit Lounge of the United Service Organizations (USO) opened in Union Terminal to care for the increasing number of troops travelling by rail. After the United States entered WWII, the number of troops moving through the Union Terminal complex exploded, reaching a war time peak of 34,000 people per day in 1944. By war’s end, the facility had served millions of troops, service personnel and their families.

Following the end of WWII, passenger train travel went into a steep decline. As airlines and highways took over as the primary means of travel in the United States, fewer and fewer trains passed through Union Terminal. By 1972, when Union Terminal closed as a train station, only two trains per day were passing through a station designed to handle 216 trains per day.

USO at Union Terminal Facts

- The Union Terminal USO lounge, the first transit lounge in the country and one of the first USO lounges established, was ahead of its time in racial integration and interfaith cooperation. In its five years of service, the Union Terminal USO lounge served nearly 3 million servicemen and servicewomen, roughly one-fifth of all World War II GIs.

- The United Service Organizations, Incorporated (USO) formed in Washington, D.C., on April 17, 1941. The Cincinnati chapter formed on May 27, setting up the "Service Room" in Union Terminal’s Rookwood Lounge on June 8.

- Local women baked pretzels, donuts and cookies, which became their signature item. The USO lounge at Union Terminal was managed by Bailey Wright Hickenlooper and had three vice-chairs, one each of Jewish, Protestant and Catholic faith. Volunteers also came from all religious backgrounds. The USO’s interfaith cooperation was well ahead of its time in the United States.

- Mrs. Harper Sibley, USO national board member and wife of the national USO president, praised Cincinnati "for being the first city in the country to sense the great need for aiding troops in transit," with the Union Terminal USO lounge "the first center to be opened for the convenience of service men."

- On January 12, 1942, the casualty room was opened in a room adjoining the Rookwood Lounge that provided six screened cots for wounded and non-wounded servicemen to rest. On Dec. 28, 1942, the USO furnished three rooms on the second floor with 55 bunk beds for soldiers to rest in.

- Unlike much of Cincinnati, the public space in Union Terminal remained integrated, including its USO lounge.

- As the number of cookies consumed reached 100,000 per month, the Cincinnati USO organized a baking and distribution schedule with volunteers from the Protestant Council of Churches, the Catholic Women’s Association and the Federation of Jewish Women’s Clubs.

- Anne Tracy, a local Cincinnati woman who had geared up activity in 1940 with visions of utilizing the Rookwood Lounge before the USO formed, was a volunteer at Union Terminal’s USO station and was asked to write a series of policies and rules for the lounge in 1943. First among the 20 guidelines was that "There is no color or racial discrimination in the service of the USO."

- Another guideline stipulated that there would be no discrimination between servicemen and servicewomen. These guidelines were modeled by other USO transit lounges across the country, 94 of which had opened by early 1943.

- To more effectively cater to the wives and families of soldiers, the Union Terminal USO set up a nursery above the Union Terminal entrance. An average of six children used this nursery each day.

- In June 1945, 72,695 soldiers spent time at the Union Terminal USO lounge, which was open 24 hours a day in 1945. The busiest month was July 1945, when 81,153 soldiers visited the Union Terminal lounge.

Source: C. Walker Gollar, Ahead of their Time: Anne Tracy and the Senior Women of the Cincinnati Union Terminal USO Lounge in Ohio Valley History, Spring 2013.