banner

CMC Blog

Roam Under the Dome

Our blog for the stories behind the exhibit, inside the film and beyond the museum.

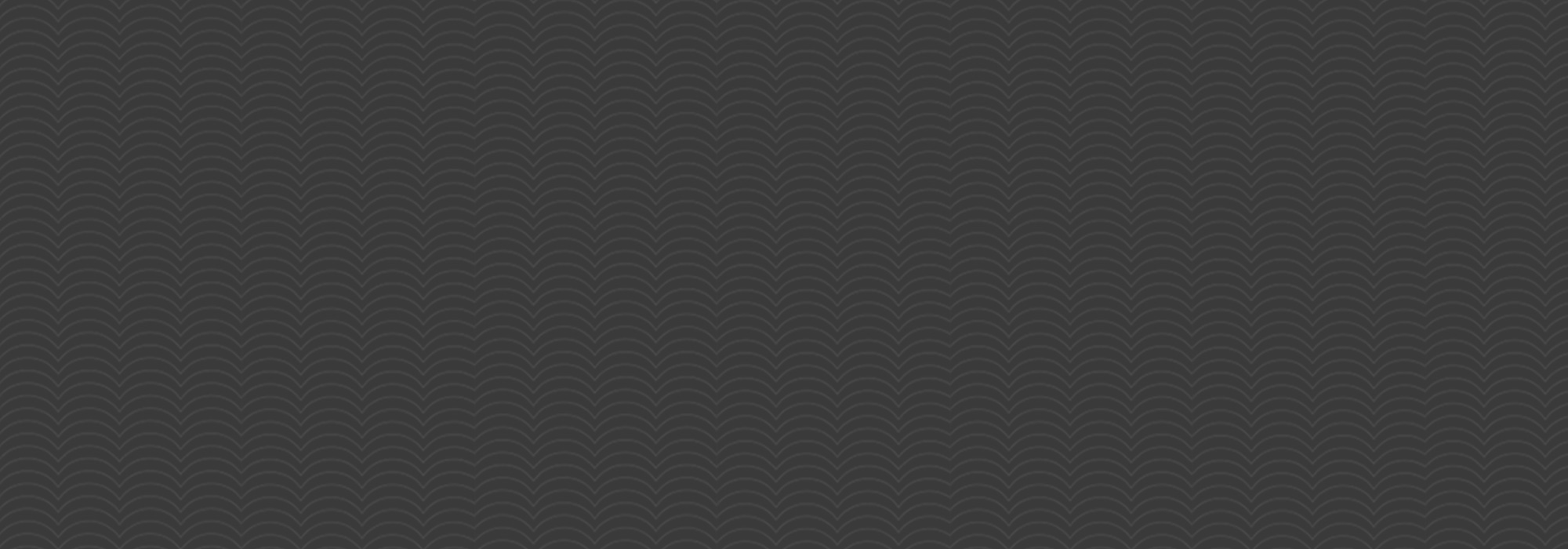

Cicadas and Locusts in the Manuscript Collection

Mickey deVise’

The impending Brood X cicada invasion prompted a search of the Cincinnati History Library and Archives for cicada related items. Keep reading to see what they found!

Cicadas and Locusts in the Cornelius J. Hauck Botanical Collection

Mickey deVise’

As the eastern portion of the United States deals with the emergence of billions of Brood X cicadas with dread and loathing, other populations around the world welcome and celebrate their existence. Find out why in our latest Off the Shelf article.

Flake-Stone Artifacts

Tyler Swinney

Archaeology is complex, multifaceted and diverse. Items of material culture are no exception as a nearly countless suite of artifacts were manufactured by prehistoric native Americans through the addition, combination and subtraction of raw materials such as stone, clay, bone, shell, wood and plant fibers.

The Fossil Fish That Could

Glenn Storrs

On December 21, 2020, Governor Mike DeWine signed Ohio Senate Bill No. 123 into law, thus designating Dunkleosteus terrelli as the Fossil Fish of Ohio. Not every state needs an official fossil fish, of course, but if you had to have one, Dunkleosteus (Dunk–ul–AHS–tee–us) might well be it, and no fish is more deserving when it comes to Ohio.

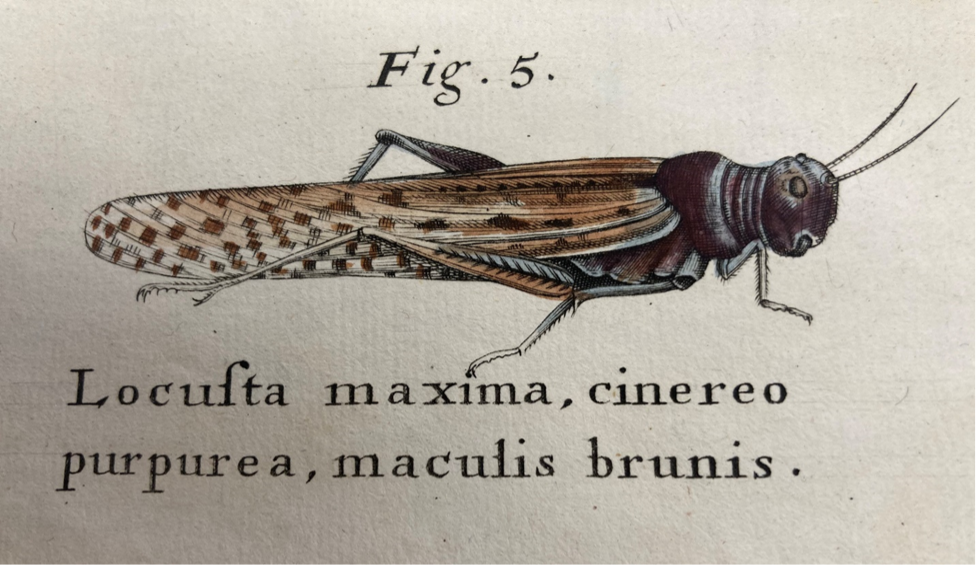

Mesa Verde National Park

Tyler Swinney

Mesa Verde is a large National Park that includes around 600 cliff dwellings which are rock and adobe structures that are built into an eroded portion of a cliff with incredible indigenous architecture and amazing landscape.

Digging Dinosaurs!

Glenn Storrs

In order to dig dinosaurs, you must first really dig dinosaurs. That is, like them a lot, because the physical digging/excavating/collecting of dinosaurs is not for the faint-hearted. It’s a grueling, exhausting, painful exercise in self-denial – until such time as the precious fossils are finally secured in the museum collection or exhibit hall.

The Official City of Cincinnati Fossil

Brenda Hunda

The Cincinnati Dry Dredgers – a group of amateur paleontologists and geologists that have collected fossils and studied paleontology in the region for over 80 years – chose five candidates for the official Cincinnati fossil.

Cincinnati’s Vanished Yellow Wares

Bob Genheimer

Their yellow colors were bright and cheerful, a sharp contrast to their dull sanitary and kitchenware predecessors – redwares and stonewares. Nineteenth-century American yellow wares, earthenwares with a buff paste and a clear glaze, were both functional and inexpensive. In most cases, they were the product of an assembly line process – a system that attempted to standardize output using relatively cheap raw materials and labor.

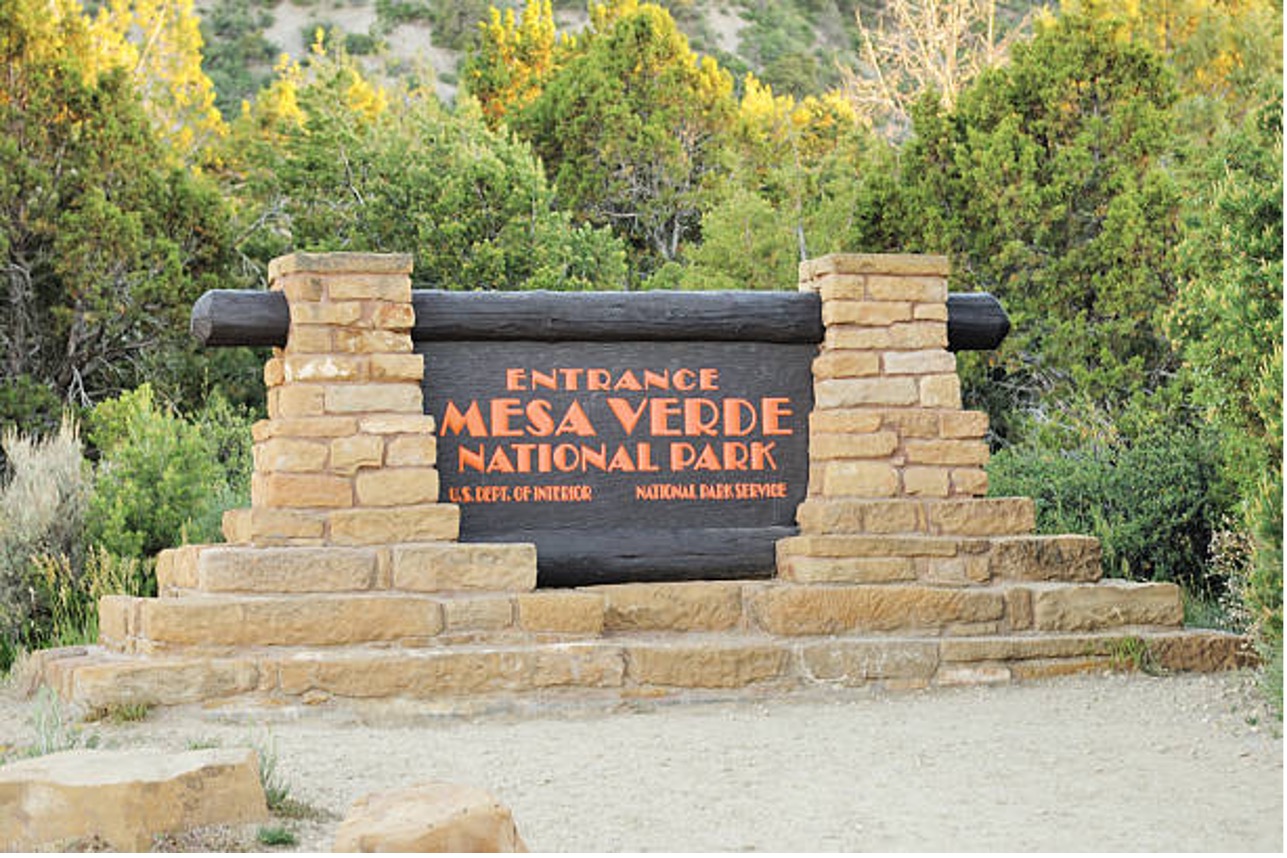

CMC’s COVID-19 Collecting Initiative

Christine Engels

Early in the pandemic, we encouraged people to document how their lives had changed due to COVID-19. We weren’t sure what we would get but we all agreed we should put out an invitation to the community to share and record these unusual times.

Where the “Buffalo” Roam(ed)

Glenn Storrs

In September 2008, CMC excavated modern bison bones (Bison bison) that had recently been discovered in the channel of Big Bone Creek, the shallow stream that traverses the valley containing the lick. Remains of at least five sub-adult animals were collected, as were a dozen Native American stone artifacts found in close association with the bones. The artifacts were identified as expedient butchering tools that had been manufactured on-site from local materials and discarded after use.

Prehistoric Bison

Glenn Storrs

Two prehistoric bison species became known to science when their fossils were discovered in Boone County, Kentucky, home of the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport and just down I-71/75 from Cincinnati. The Giant Bison, Bison latifrons, was identified from a skull fragment found around 1800 in the bed of a stream, likely either Gunpowder or Woolper Creek.

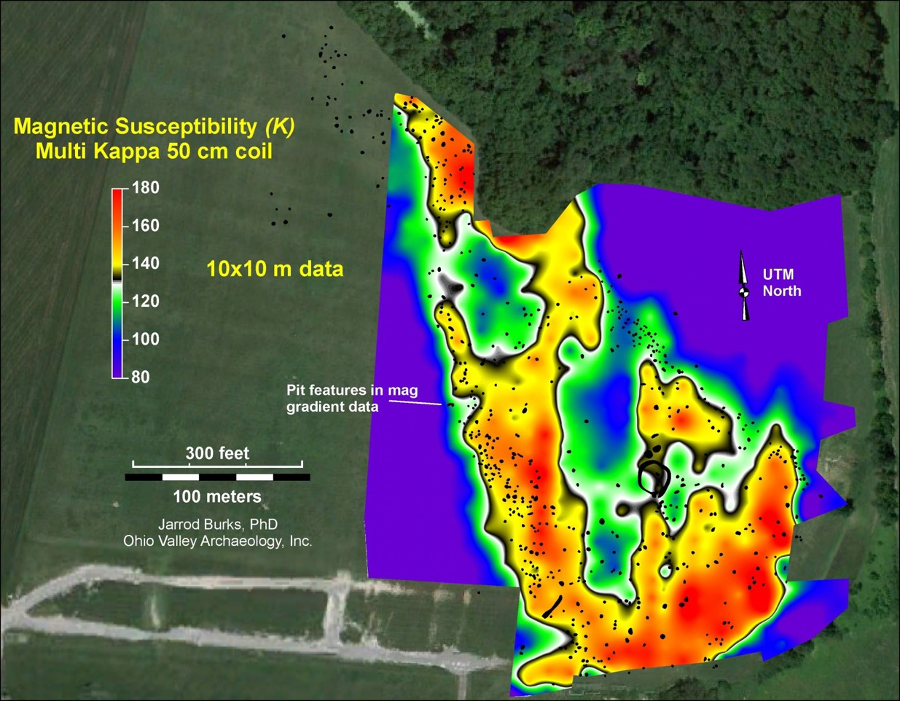

Seeing Beneath the Ground: Remote Sensing at the Hahn Site

Bob Genheimer

You may wonder how Cincinnati Museum Center’s archaeologists decide where to dig when we excavate a site. In part, our decisions are based on which questions we are trying to answer (e.g. what did they eat, how did they cook, what were their houses like, etc.), and on how much we can accomplish within a short amount of time. But, to answer most of these questions, it is helpful to know with some accuracy what lies beneath the surface. For this, we turn to ground-based remote sensing, also known as archaeological geophysics.

Maya Mammals (and more!)

Emily Imhoff

If you visit Maya: The Exhibition, one thing you will notice is how often animals are represented in the artifacts shown, and even in the glyphs used in their ancient writing system. Historic and modern cultures all around the world often use images of animals in their art and to decorate everyday objects. These animals might be important food sources, or religious or cultural symbols, or even pets.

Encrustation! Species Interaction in the Fossil Record

Brenda Hunda

Encrusted fossil specimens are important because they provide direct evidence of species interaction at a single point in geological time. With this information, paleontologists can reconstruct community composition, the ecological roles of various fossil organisms and the biological implications of such interactions.

That can’t be good! (for a fossil)

Glenn Storrs

Why then would anyone want to damage a fossil bone by removing a section of it with a power drill? Surely this must be a wanton act of vandalism! Read our latest blog entry to learn why museums sometimes have to break a few eggs to make an omelet and drill a few bones to make a discovery.