CMC Blog

Cicadas and Locusts in the Cornelius J. Hauck Botanical Collection

By: Mickey deVise’, Reference Librarian

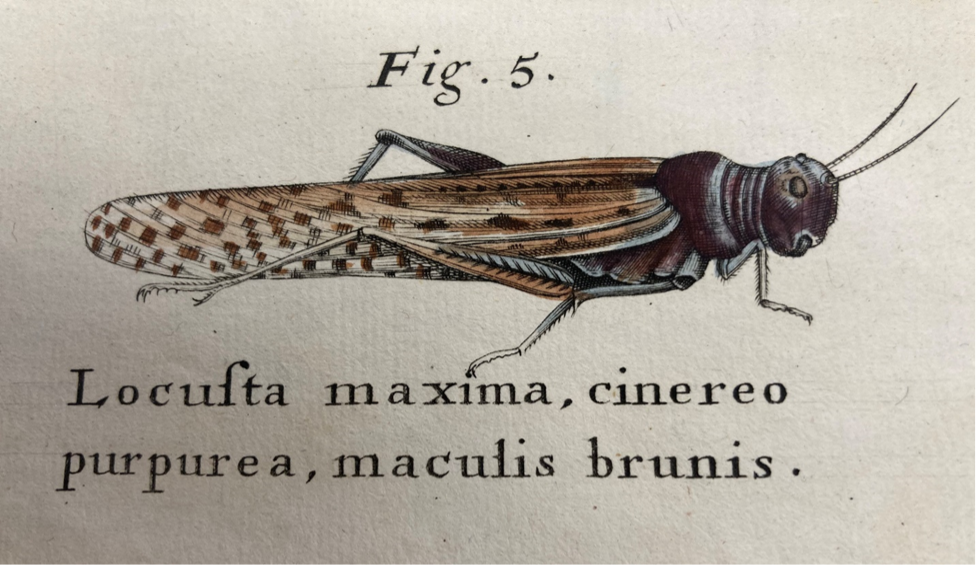

Locusta maxima copper plate engraving: Figure 5; Hans Sloane, 1707 Voyage to the Islands of Madera; CMC Printed works collection

As the eastern portion of the United States deals with the emergence of billions of Brood X cicadasi with dread and loathing, other populations around the world welcome and celebrate their existence. A search of the printed works collection of the Cincinnati History Library and Archives revealed illustrations and texts related to cicadas and locusts in the Cornelius J. Hauck Botanical Collection. These accounts from around the world range from destruction caused by their periodic appearance to how one can prepare them as food.

In Our Common Insects (1873), V.T. Chambers is quoted as saying “it is abounding with locusts in June,” in the vicinity of Covington, Kentucky, “in common with a large portion of the Western Country.”. Professor Orton from Yellow Springs, Ohio is quoted as saying that because of damage done by this insect, “many of the orchards have lost two full years growth.” Mr. L. B. Case of Richmond, Indiana states that “people are greatly alarmed about them; some say they are Egyptian locusts.” Packard refers to them as 17-year locusts in his description.ii

Local cicada expert Dr. Gene Kritsky explains the difference between locusts and cicadas is that locusts are grasshoppers while cicadas more closely resemble aphids. Early British colonists living here first started using the term locusts incorrectly, when cicada infestations reminded them of the Biblical plagues of Egypt. Locusts are more destructive than cicadas as they feed on a large array of plant life, leaving devastation in their wake.iii

One stunning monograph in the Hauck Collection is the two-volume set written from 1707 to 1725 by Hans Sloane, M.D. (1660-1753) titled A Voyage To The Islands of Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Christophers And Jamaica; Illustrated with the Figures of the Things describ’d which have not been heretofore engraved; In large Copper-plates as big as the Life [sic]. This flat folio contains thousands of images of flora and fauna of the region, with many of them indeed life size. The colors of the huge fold-out, 300-year-old drawings are as gorgeous and vibrant as if they were engraved yesterday.iv

Sloane’s habit of collecting natural curiosities led him to the field of medicine and later the Caribbean, accompanying the incoming governor of Jamaica. There he collected thousands of specimens including cacao and Peruvian bark. He is credited with making chocolate milk from cacao and extracting quinine from Peruvian bark to treat eye ailments. Sloane bequeathed his lifelong assortment of 71,000 items to Britain, which became the founding collection of the British Museum.v

Sloane’s paragraphs on cicadas begin by noting that Aristotle “does extremely extol young soft Cicadae in his History of Animals, and the time to kill them to the best Advantage, is the Males ante coitum, and the Females after, when they are most savoury [sic].” He tells us that Athenus speaks of a marriage dinner where one of the greatest dishes was ‘Cicadae’ salted and dried.vi He is certain that while locusts and grasshoppers are a curse to most places as they devour the fruits of the earth, they are a great blessing to other places where the inhabitants are destitute of other provisions. They are dried in an oven, or salted and kept, or powdered and ‘mixt’ with milk, and, as he has been told, they eat like Shrimps. West Indians dine on grilled cicadae, crickets, grasshoppers and locusts. Sloane includes a thorough, colorful description of locusts and the illustration above. He writes about how locusts cover the ground and obscure the air every third or fourth year, destroying all in Ethiopia, where they salt and eat them.vii

Another extraordinary monograph is Descriptions of the Animals, Birds, Amphibians, Fish, Insects, Worms, which Petrus Forskal observed on his journey through the East. Written in Latin and Arabic, it is considered the earliest accurate and detailed description of botany in the Near East and a very fine account of natural life in Egypt and Arabia. The Swedish author died of the plague in Arabia in 1763 at age 27 before the book was published in Copenhagen in 1775. The dedication reads “For the most serene and powerful leader, King Christian the Seventh, ruler of the Danes, Norwegians, Vandals, Goths, and all the rest.” And “Peter Forskal, made known to posterity by this posthumous work, will live forever – either praised or excused.”viii

Here is the translation of the passage regarding cicadas: "When I traveled to the Greek Monastery called Raithu, in the famous area known as Elim, a priest reported to me that Manna falls in the winter season along with the rain, and it is of the same type as the blessed substance which fell from the sky for the Israelites. He added also, with the faith of a monk, that this precipitation was found nowhere besides on the roof and grounds of the monastery, and that he himself had often seen and tasted it. Here my belief halted. Our learned men, who are able to explain miracles with the slightest knowledge of natural science and shake out this Manna-bearing rain from the mouths of Cicadas, would search intently for the same explanation in these places, which are bare and scarcely covered with small produce, and where I and my travel companions saw the largest Cicadas we have ever seen. Since the place abounds in gardens of date palms, the cause of this precipitation appears instead to be congruous with nature." ix

To the ancient Greeks, the song of the cicada was the pinnacle of beauty. They associated their most elegant and celebrated poets and the Muses themselves with the cicada. The Romans were not quite so enthusiastic about its noise, but there are far more ancient texts expressing appreciation for cicada music than annoyance at it.x How appropriate that cicada acoustics have long been compared to music. The hollow, air filled spaces of a cicada body act like a resonating chamber, amplifying the dissonance they create, much like a guitar or other string instrument.xi The chicarra [cicada] is the voice of nature. When the first chicarra sings, whether it has rained or not, the vegetation is glad, as if rejoicing with them means being filled with green tenderness.xii

Many thanks to Dr. Caitlin Hines and Dr. Marion Kruse from the University of Cincinnati Classics Department for their translation of Latin text in Forskal’s work. To Dr. Hines for the Greek and Roman references. Dr. Mauricio Espinoza, Assistant Professor of Spanish and Latin American Literature at UC for the translation of the El Impulso text about chicarras. Sammy Ali of Cincinnati Museum Center for his translation of Arabic text in Forskal.

i Cicadasafari.org [Accessed May 16, 2021]

ii A. S. Packard, Jr., Our Common Insects, (Boston: The Salem Press, 1873), pp. 212-215.

iii Cicadasafari.org [Accessed May 16, 2021]

iv Hans Sloane, M.D., A Voyage To The Iflands of Madera, Barbados, Nieves, S. Chriftophers And Jamaica, vol. 1 (London: Printed by B.M. for the Author, 1707)

v https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/sir-hans-sloane [Accessed May 16, 2021]

vi Sloane, p. XXVI.

vii ibid, p. 29.

viii Petrus [Peter] Forskal, Descriptions of the Animals, Birds, Amphibians, Fish, Insects, Worms, which Petrus Forskal observed on his journey through the East, (Copenhagen: Molleri, 1775) notes.

ix Forskal, p. XXIII.

x Email correspondence from Dr. Caitlin Hines, University of Cincinnati Classics Department, May 17, 2021.

xi Gene Hall, quoted by Daniel Stolte, https://news.arizona.edu/story/7-things-you-didnt-know-about-cicadas (Accessed May 23, 2021)

xii https://www.elimpulso.com/2012/04/10/lectura-las-chicharras/ (Accessed may 17, 2021)

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children's Museum

| Adult: | $22.50 |

| Senior: | $15.50 |

| Child: | $15.50 |

| Member Adult: |

FREE |

| Member Child: |

FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.