CMC Blog

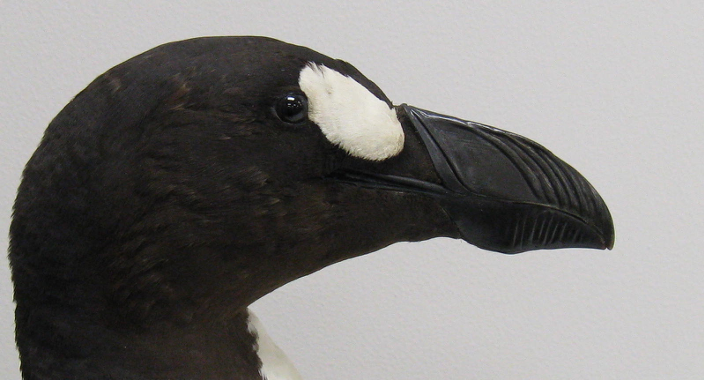

Is this the last Great Auk?

By: Heather Farrington, Curator of Zoology

The Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis) was a penguin-like, flightless bird found along coastlines in the north Atlantic. It was valued for its meat, fatty oils, and feathers, and was hunted to extinction in the mid-1800’s. As the bird became more rare, collectors paid handsomely for specimens. In 1844, the last documented Great Auks (a breeding pair) were captured at Eldey Rock, an island off the coast of Iceland. Their egg was crushed, and the birds were killed and their carcasses were sold on the mainland. When the birds were skinned, some soft tissues from each were preserved in alcohol and ended up in the fluid collections of the Natural History Museum of Denmark. The fate of the skins of these last known birds remained a mystery until 2017, when an international team of scientists released their findings of an investigation into this question.

The researchers extracted DNA from the preserved soft tissues of both the male and female bird and set about trying to find genetic matches with the 80+ known remaining Great Auk skins held in collections worldwide. To narrow the search, historical sale and auction records and personal correspondence were used to track the history of each specimen. This research led to five possible skins, which were sampled, genetically analyzed, and compared to the DNA from the soft tissues in Denmark. Of these five birds, one matching the male soft tissue sample was found – the taxidermied skin held at the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique in Brussels, Belgium, known as the ‘Brussels Auk.’ There was no match found for the female soft tissue sample.

Due to historical documentation, the researchers were confident that the female Great Auk skin was one of four sold in London in the 1970s. One of those was purchased for Cincinnati and is held in our Zoology Collection. After the researchers published their paper, they contacted us to request a tissue sample from our Great Auk to determine whether it was the last female. We agreed to provide a tissue sample to hopefully solve this great mystery!

We needed to take a sample that would be minimally destructive to the specimen, leaving no visible damage – the underside of the foot is a commonly used spot. We drilled a hole in the wood and plaster base to give us access to the bottom of the foot, then inserted a scalpel to cut off a sliver of the foot pad. We also collected two feathers from the flank for additional samples. All samples were then sent to the researchers for analysis.

We anxiously await the results of the genetic analysis! A huge thank you to the researchers who were willing to extend their study with our specimen to get to the bottom of this mystery. When we get the results, we’ll post a follow-up blog to let you know the results. Stay tuned!

In the meantime, here is a link to the published article - https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/8/6/164.

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children’s Museum.

| Adult (13+): | |

| Senior (60+): | |

| Child (3-12): | |

| Member Adult: | FREE |

| Member Child: | FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.