Incredible photos from The Cincinnati Ballet, now a part of CMC’s Photographs, Prints and Media archives.

[READ MORE]Author Archive: Jessica Prater

Cincinnati Museum Center and the Cincinnati Zoo Team Up to Evaluate Population Recovery of Cumberland Sandwort

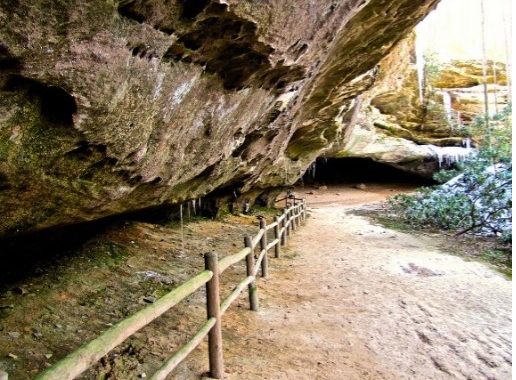

Learn how conservation techniques have been used to produce a supplemental outplanting of the rare Cumberland Sandwort! The Cumberland Sandwort is an herbaceous perennial known to occur exclusively in the Cumberland Plateau of southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee.

[READ MORE]Voices of Cincinnati’s Past – Digitizing Cincinnati Museum Center’s Rare Radio Show Collection

Cincinnati Museum Center is fortunate enough to care for and permanently house a rare collection of original Cincinnati radio transcription discs from local radio stations, including the well-known WLW-WSAI Broadcasting Corporation. Keep reading to find out more about this rare piece of history!

[READ MORE]Growing through Ohio History Day

Ohio History Day inspired me, opened me up to opportunities and challenged me in ways I never would have thought possible. The experience has been transformative and has illuminated passions I likely would never have discovered otherwise. Thank you, Ohio History Day!

Cincinnati Museum Center is proud to organize and host Ohio History Day’s Region 8 competition for Adams, Butler, Clermont, Clinton, Hamilton, Highland and Warren counties.

[READ MORE]Going Batty in Cincinnati

Big brown bats are just one of over 1,400 bat species found all over the world, some of which call Cincinnati Museum Center home. Keep reading to learn more about these denizens of the dark.

[READ MORE]Clovernook and the Trader Sisters

The Trader sisters worked to help blind and visually impaired people live an independent life in their own homes. Read more to learn how they did it!

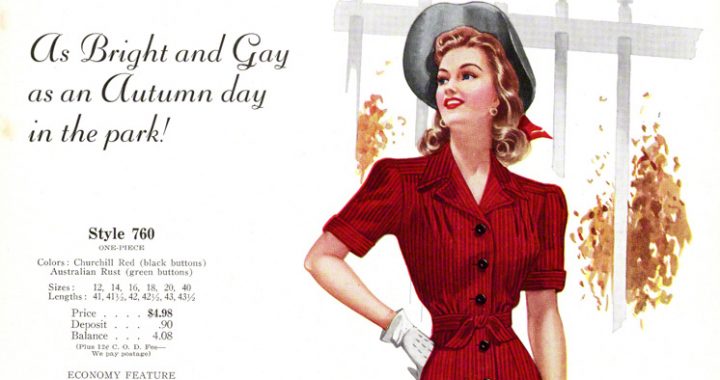

[READ MORE]Fashion Frocks

Philip M. Meyers started working for his father’s Princess Garment Company in 1922. He left in 1925 to found his own company, Fashion Frocks, Inc., a garment manufacturer that directly sold to consumers.

[READ MORE]Super-Volunteer: Minnie “Dolly” Varley

Minnie “Dolly” Anson was born on June 25, 1904 in England. Inspired by her own mother, who was a long-time volunteer for the Red Cross, Dolly joined the Junior Red Cross while living in Australia.

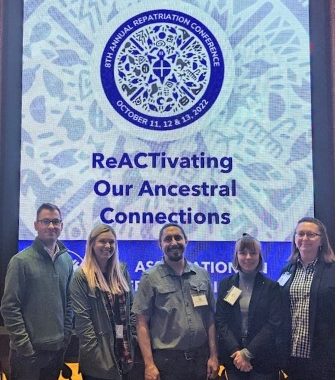

[READ MORE]Introduction to NAGPRA

At its core, NAGPRA is human rights legislation that was enacted by congress to addresses inequalities between federally recognized descendant communities, the US government, and institutions that control ancestral remains and cultural items affiliated with sovereign Tribal Nations indigenous to the United States. NAGPRA also establishes procedures for inadvertent discoveries on federal and tribal lands and makes it illegal to traffic ancestral remains and cultural items obtained through activities that violate the Act.

[READ MORE]New Motus tower at Edge of Appalachia Preserve System

Long-distance movements of animals, like the seasonal migration of birds, have always intrigued scientists. When animals leave our region, where do they go and why?

[READ MORE]