CMC Blog

The Queen City welcomes Charles Lindbergh and is Spirit of St. Louis, August 6, 1927

By: Scott Gampfer, Associate Vice President for Collections & Preservation

The Spirit of St. Louis at Lunken Field, August 6, 1927. CMC Photograph Collection.

Charles A. Lindbergh, an obscure 25-year-old air mail pilot, became an international celebrity when he became the first aviator to cross the Atlantic Ocean non-stop from New York to Paris, France. He made the successful crossing on May 20-21, 1927, flying solo in a single-engine Ryan monoplane nicknamed the Spirit of St. Louis in a little over 33 hours. When Lindbergh landed in Paris, his life changed forever. Crowds mobbed his plane even before it had come to a stop. People rushed forward to get a glimpse of the daring American aviator and his plane. Lindbergh was virtually pulled out of his plane and carried around by the cheering crowd.

After a few brief flights in Europe in the Spirit, Lindbergh returned to the United States where he received a medal from President Calvin Coolidge in Washington, D.C., followed by a ticker-tape parade in New York City two days later. The adulation of Lindbergh and the desire to see him in person and to hear him speak was just getting started.

Lindbergh was not a person comfortable with the limelight, but he was interested in promoting aviation and realized that there was an opportunity for him to do that using his new-found fame. Lindbergh and Harry Guggenheim, the millionaire philanthropist whom Lindbergh had met before his successful New York to Paris flight, conceived of a national air tour in the Spirit of St. Louis. With the financial backing of the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics, a plan was drawn up for Lindbergh to visit at least one city in each of the 48 states. Starting on July 20, 1927 and continuing through October 23, 1927, Lindbergh and the Spirit visited 82 cities and covered some 22,000 air miles in over 260 hours of flying. Lindbergh, the man never comfortable in front of a crowd, gave 147 speeches during the tour and rode approximately 1,290 miles in parades.

In laying out the tour, it was agreed that Lindbergh would make stops at three cities in Ohio; Cleveland, Dayton and Cincinnati. Once a Cincinnati stop was set, a “Committee of Arrangements” of the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce was formed and began working out the local details. There was much excitement in the Queen City at the prospect of a visit by the famed aviator and his equally famous aircraft. Plans were developed for Lindbergh to land at Lunken Field and to be conveyed by motorcade to Redland Field where a public reception would be held. The committee arranged for a section of the grandstands to be reserved specifically for children because “the children of today will be the aeronaut of the future.”

Col. C.O. Sherrill, Cincinnati City Manager, assigned 400 special policemen and about 200 uniformed firemen to the ball park to handle the expected large crowd and to prevent the crowd from rushing the air hero upon his arrival. The Boy Scouts of Cincinnati were delegated by the Committee of Arrangements to act as the “personal guard” to Lindbergh.

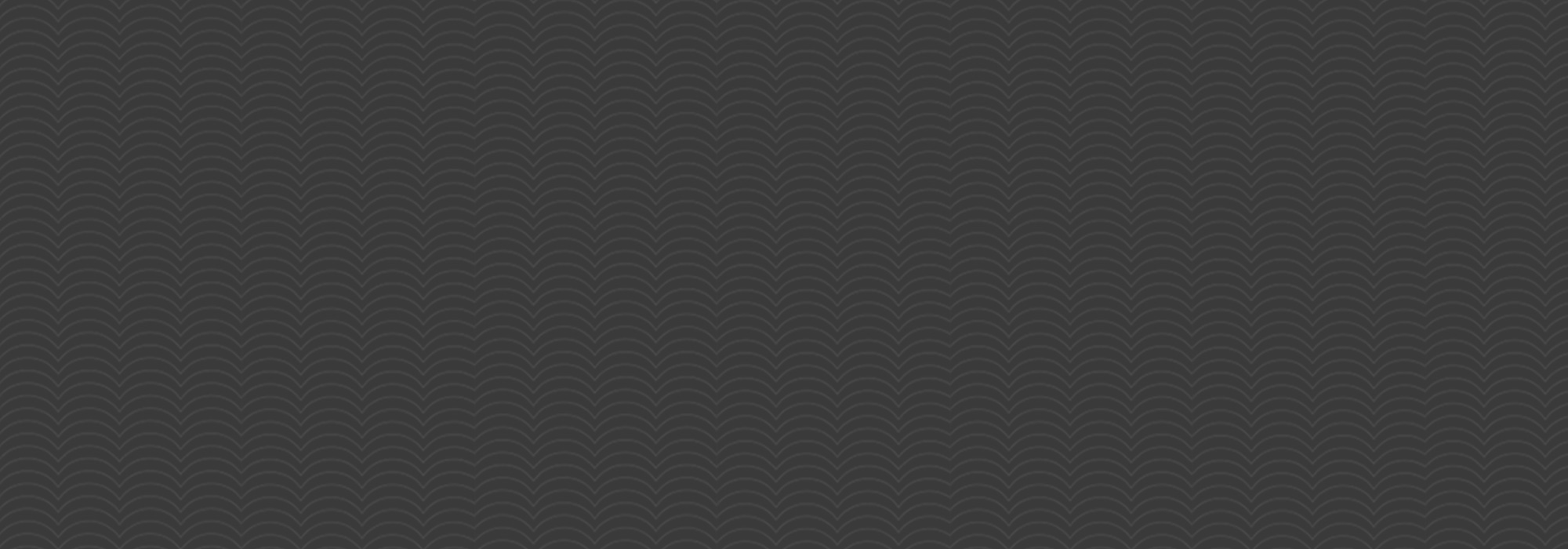

Cincinnati Enquirer, August 6, 1927

The Chamber’s Civic Secretary, Howard M. Wilson, attended a conference with Lindbergh and his tour manager on Friday, August 5 in Dayton, Ohio, to iron out the final details of his arrival in Cincinnati the next day. Lindbergh was particularly pleased when informed by Wilson that some 10,000 school children were expected to be at Redland Field to greet him. It was agreed that there would be no ceremony at Lunken Field other than a handshake and greeting by Vice Mayor Stanley Matthews as the aviator climbed out of his plane. Lindbergh would be transferred at once to a waiting automobile for the procession to the ball park.

At the conference Lindbergh insisted that no other airplanes be flying in the vicinity of Lunken Field when he arrived for safety reasons and Mr. Wilson assured him that no planes would be in the air after 12 o’clock noon until he landed safely.

During the air tour, Lindbergh was accompanied by another aircraft, provided by the Guggenheim Fund and the U.S. Department of Commerce, to carry the tour manager Donald H. Keyhoe and Phil R. Love, a close friend of Lindbergh and a former air mail pilot. The “large red monoplane” was piloted by T.H. Sorensen and would arrive at each location about a half-hour prior to the arrival of Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis.

On August 5, Lindbergh flew from Wheeling, West Virginia to Dayton. He departed Dayton the next day for Cincinnati and chose a route that took him over Franklin, Middletown and Hamilton. Because the number of planned stops on the air tour was limited, many cities and towns were disappointed at being left out and requested that Lindbergh at least fly over their town enroute from one stop to another. When possible, Lindbergh flew over and often circled towns along the way.

The local newspapers reported that August 6 was a great day for the city and everyone was abuzz with excitement even before Lindbergh arrived over Lunken Field. When he did arrive from Dayton, “Lindy flashed over Lunken Field in a vertical bank over the heads of the crowd assembled there, soon after circling over downtown Cincinnati and the hills of Northern Kentucky.” At 2 p.m., “The Spirit of St. Louis swooped onto Lunken Field and taxied to its stopping point, amid the noise of automobile horns and the plaudits of the many thousand men, women, and children who waited there to greet him.” Apparently, the enthusiastic crowd surged past police lines and almost ran in front of Lindbergh’s plane before order could be restored.

Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis at Lunken Field August 6, 1927. CMC Photograph Collection.

(L-R) Howard M. Wilson, Charles A. Hinsch and Lindbergh after his arrival at Lunken Field, August 6, 1927. CMC Photograph Collection

Lindbergh, wearing a leather flying coat and flying helmet, was greeted by the Vice Mayor and other officials as he climbed from his plane. He was quickly directed to an open car which occupied the front rank of a motorcade of official vehicles led by a motorcycle escort, and conveyed to Redland Field along a ten-mile route through Hyde Park, Walnut Hills and Downtown. Crowds lined the route hoping to get a glimpse of the famous flyer.

Lindbergh (second from right) leaving Lunken Field in motorcade, August 6, 1927. CMC Photograph Collection.

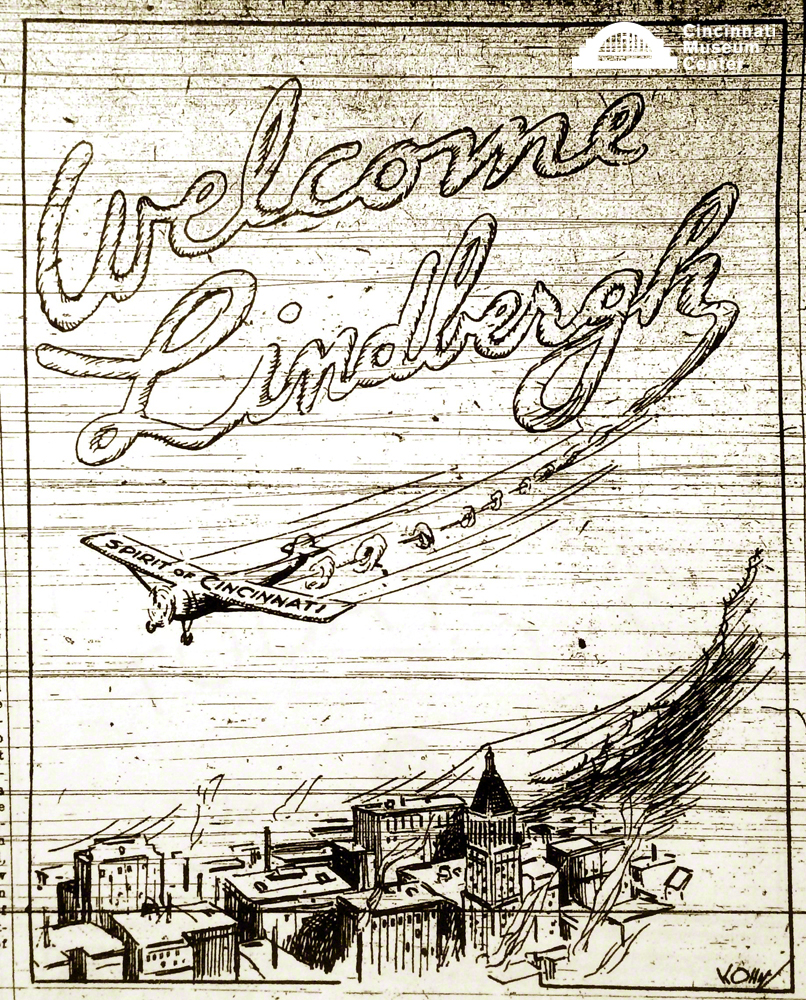

Windshield sign for motorcade vehicles. CMC Ephemera Collection.

Once at the ball park, Lindbergh was taken to a temporary platform that had been erected for his use in addressing the assembled crowds in the grandstands. The platform, equipped with amplifiers to magnify his voice, was decorated with American flags, red, white and blue bunting and even a large framed portrait of Lindbergh. As Lindbergh and his party made their way to the speaker’s platform, their progress was accompanied by continuous waves of cheering from the crowd. As the party reached their places on the platform, the cheering stopped while the band played the Star-Spangled Banner, but resumed immediately as the national anthem concluded. The band then played “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem, before remarks began.

Introductions were made and Lindbergh was presented formally with a ceremonial Native American eagle feather headdress by three local Boy Scouts. He posed briefly wearing the headdress while photographers and motion picture cameramen captured the scene. After opening remarks by Vice Mayor Matthews, Lindbergh gave his speech, likely the same speech, or a version of the same speech, he gave at each stop. Lindbergh spoke directly into the microphones so that all could hear as he talked about the recent accomplishments in commercial aviation and predicted great progress with commercial passenger service. He urged the city of Cincinnati to get behind an air program that would keep the city “on the air map” of the country. His remarks lasted only about five minutes and the entire program around 15 minutes.

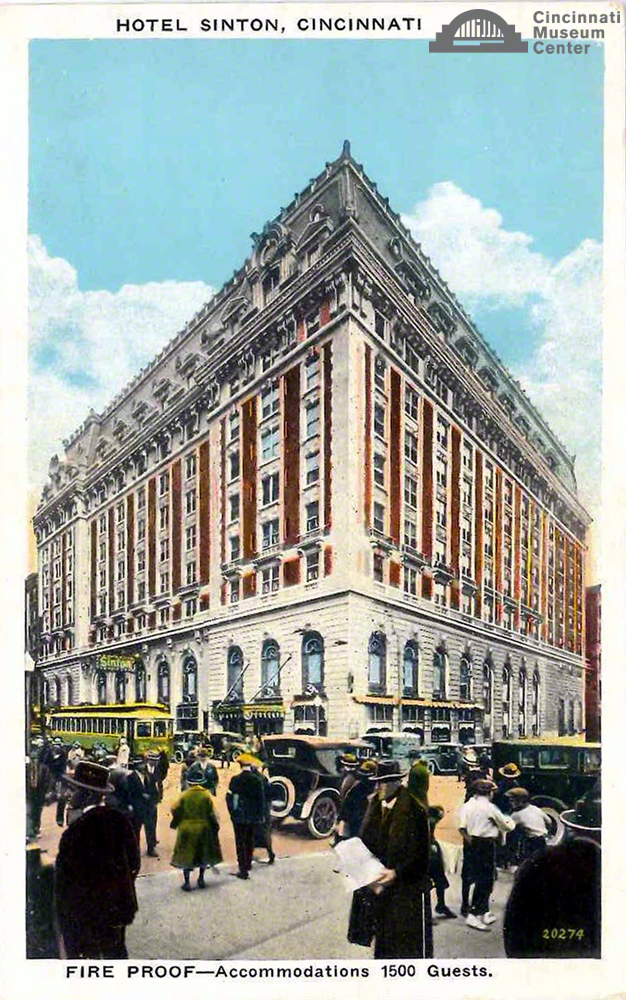

Following the ceremonies at Redland Field, Lindbergh was taken downtown to the Hotel Sinton where a brief period was set aside for the local press representatives to interview him and where he could then rest. Arrangements had been made for him to stay at the Sinton while in town and he apparently was offered the presidential suite. That evening a testimonial dinner was held at the roof garden of the Hotel Gibson. Local Camp Fire Girls had been enlisted to make penguin table decorations for the banquet. Seated among the many guests at the speaker’s table were Vice Mayor Matthews, City Manager Sherrill, tour manager Donald Keyhoe, Postmaster A. L. Behymer and Powel Crosley. The crowd of 1400 rose to their feet and applauded when the Vice Mayor told Lindbergh “that his modesty and exemplary character have made him the ideal of all American youth.”

Lindbergh (third from right on platform) at Redland Field, August 6, 1927. CMC Photograph Collection.

Periodically during the Guggenheim tour, Lindbergh and his manager inserted “rest days” so the flyer could get a break from the crowds and attend to personal business. Sunday, August 7 was a rest day for Lindbergh which he spent in Cincinnati. He wasn’t scheduled to depart for his next stop at Louisville, Kentucky until Monday, although the exact time of his departure was kept from the public so as to avoid attracting a large crowd.

Postcard of the Hotel Sinton at Fourth and Vine Streets. CMC Photograph Collection.

Lindbergh spent Sunday morning conferring with his tour manager Kehoe regarding the details of his upcoming flight to Louisville and he also spent some time going through his mail. Later, after lunch, “the ‘Flying Colonel’ took an automobile ride through the western parts of Cincinnati and expressed himself as delighted with the beautiful homes and picturesque scenery.” In addition to Lindbergh, passengers on the automobile excursion included his tour party of Kehoe, Sorensen and Love with local car dealer H. F. Fulton handling the wheel. At some point, Fulton relinquished the driver’s seat to Lindbergh who drove the party to Lunken Field so he could check on the Spirit. When the crowd that was gathered to view the plane recognized the famous flyer, they cheered and Lindbergh obligingly bowed.

Early Monday morning, August 8, Lindbergh arrived at Lunken Field to begin preparing the Spirit for its flight to the next stop on the tour, Louisville Kentucky. Lindbergh was scheduled to depart Lunken at 1 p.m. and arrive at Louisville’s Bowman Field around 2. He wanted to allow plenty of time to have his ship refueled, replenish the engine oil and conduct a thorough pre-flight examination of the craft as was his custom. The Spirit of St. Louis had remained at Lunken Field ever since its arrival on Saturday, August 6. Following Lindbergh’s departure for Redland Field, and during the day on Sunday, the plane had been out for public viewing surrounded by temporary fencing, decorated with red, white and blue bunting. This measure was necessary to keep the public at a safe distance from the famous monoplane, but still allow it to be viewed and photographed. The aircraft was guarded the entire time by soldiers posted inside the fencing.

While performing a detailed examination of his plane, Lindbergh discovered that particularly bold souvenir hunters had somehow sneaked past inattentive guards and cut an approximately one-square-foot section of fabric from one of the wings, leaving a large hole. The plane was towed to a hangar where experts patched the wing with materials brought down by plane from the Army’s Wilbur Wright Field in Dayton.

While waiting for the machine to be serviced and repaired, Lindbergh treated two of his hosts to an unexpected thrill. Charles A. Hinsch, chairman of the Lindbergh entertainment committee, and Howard Wilson of the Chamber of Commerce had come with Lindbergh to Lunken that morning. Borrowing a plane from Embry-Riddle, Lindbergh took the two of them for a thrilling flight over the city which included a few aerobatic “stunts” thrown in for good measure.

Lindbergh pulling the propeller through on the Spirit to clear the lower cylinders before departing for Louisville. CMC Photograph Collection.

By approximately 1 p.m., both Lindbergh and his plane were ready to depart for Louisville. The red monoplane carrying tour manager Keyhoe had departed Lunken around 12:30 so it would get to Louisville ahead of him. With the roar of its Wright Whirlwind motor, the silvery Spirit of St. Louis with Charles Lindbergh at the controls climbed into the air and set course for Louisville. At exactly 2:02 p.m. Lindbergh glided in for a landing on the turf at Bowman Field after circling the city and was again greeted by a huge enthusiastic crowd.

For Lindbergh the tour continued, but for Cincinnati the excitement was over. Thousands of citizens of the Queen City, at Lunken Field, at the ball park, at the banquet and all along the route that the famous aviator took through the city, got an experience they never forgot. Large numbers of locals who were able to get to Lunken Field to see the aviator or simply view his plane, brought cameras to record what they saw. Many of the photographs captured of Lindbergh’s visit have found their way into the collections of the Cincinnati History Library and Archives over the decades since 1927. Howard Wilson’s daughter Sonja donated a number of interesting things from her father’s time with Lindbergh, including the “Official Car” sign from the Lindbergh motorcade (depicted in the article) and the collections contain a few examples of the many Lindbergh souvenirs marketed all over the country to Americans following the New York to Paris flight. People clamored to own anything bearing the image of Lindbergh or his famous Ryan monoplane, the Spirit of St. Louis.

Lindbergh wrapped up the Guggenheim air tour of the country on October 23, 1927 when he touched down at Mitchel Field, Long Island, New York. This was the same field where it all started on July 20. Lindbergh made a second air tour of Latin America from December 1927 to February 1928, after which he donated the Spirit of St. Louis to the Smithsonian Institution for a well-earned rest.

Souvenir plate and airplane pin commemorating Lindbergh’s New York to Paris Flight. CMC History Objects Collection

References:

McCook Field 1917-1927: The Force Behind America’s Golden Age of Flight, Mary Ann Johnson, Dayton, 2002, p.306-311.

“Lindbergh Will Visit Cincinnati on Aug. 6th,” The Cincinnatian, August 1927, p.15.

“Stunts to be Lindbergh Way of Showing Appreciation of Cincinnati Welcome,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, Saturday, August 6, 1927, p.1. Ibid.

“Guggenheim Tour – 48 States, Visited 92 Cities…,” Charles Lindbergh American Aviator, www.charleslindbergh.com. Copyright 2014. (Note: Website contains tour itinerary from Charles A. Lindbergh’s “Spirit of St. Louis.”)

The Cincinnati Enquirer, Sunday, August 7, 1927, p.1.

Images of Aviation: Lunken Airfield, Stephen Johnson and Cheryl Bauer, Arcadia Publishing. Charleston, South Carolina, 2012, p.50.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, Sunday, August 7, 1927, p.26

Images of Aviation: Lunken Airfield, Stephen Johnson and Cheryl Bauer, Arcadia Publishing. Charleston, South Carolina, 2012, p.51.

Cincinnati Times-Star, Monday, August 8, 1927, p.1. Ibid.

“Lindbergh Greeted by 100,000 Here,” The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky, Tuesday, August 9, 1927, p.1.

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children's Museum

| Adult: | $22.50 |

| Senior: | $15.50 |

| Child: | $15.50 |

| Member Adult: |

FREE |

| Member Child: |

FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.