CMC Blog

The Spanish Flu

By: Jill Beitz, Manager of Reference and Research, Cincinnati History Library and Archives

“The people are tired of hearing of the influenza and want to forget it. The psychological time for raising the restrictions has arrived. You can no more control the people’s enthusiasm and regulate their actions on the street than you can the Ohio River.” Cincinnati Mayor John Galvin, November 11, 1918.

In the midst of the 1918 influenza pandemic, Cincinnati’s Mayor made the decision to give up. There was pressure from businesses, saloons, clergy and citizens to allow them to get back to normal daily life. How did the city get to this point and what happened before and after?

On September 11, 1918, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that the influenza outbreak in Boston was expected to make its way down the East coast and so would likely arrive soon in Cincinnati. The Enquirer assured people that “at its worst, influenza causes discomfort for only a few days.” This was unequivocally wrong. While it took a few weeks for cases to start appearing in Cincinnati, once it got rolling things happened quickly.

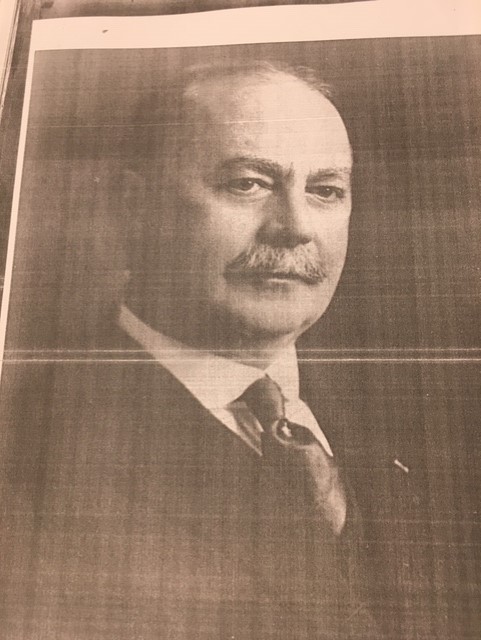

On October 3, Cincinnati Health Officer William H. Peters barred all hospital visitors except those visiting critical patients and asked people to stay away from theaters, movie houses and public events even though there was “no cause for alarm.” Two days later, they decided that there was cause for alarm and closed all theaters, movies houses, schools, churches and banned private meetings. Saloons were only allowed to sell alcohol in bottles, and it could not be consumed on the premises. Staff physicians, nurses and interns at General Hospital were required to wear masks while other hospital employees were required to gargle three times a day.

By October 10, it was estimated that there were between 4,000 and 5,000 cases in the city. The north wing of Music Hall had been appropriated for use as a hospital ward and held 85 cases. And yet, Peters reported that the closures had saved hundreds of lives and the epidemic would be over in ten days!

Four days later the cases and fatalities were at their highest level. Peters attributed this to the burning of leaves and placed a ban on the practice. The numbers continued to climb over the next few weeks. In fact, even Peters was infected.

Peters’ replacement tried to tighten up the restrictions by removing all chairs and sofas from lobbies of hotels to prevent loitering, stepping up a police presence in saloons that were violating the rules and mandating that all barbers and hotel workers wear masks. This seemed to help because by the last week in October it seemed like they were turning the corner. At this point, the rules relaxed a bit, so orphans were taken in, penny lunch rooms were opened for suffering families and volunteers began taking convalescent victims for rides in the countryside.

On October 27, Peters returned to his position and estimated cases numbering between 20,000 to 25,000. At the same time, Superintendent Walter List of General Hospital demanded that saloons and five and dime stores be closed. Peters wanted to loosen restrictions due to pressure from clergy and others, but the Board of Health refused and in fact limited shop hours and banned the sale of secondhand clothes.

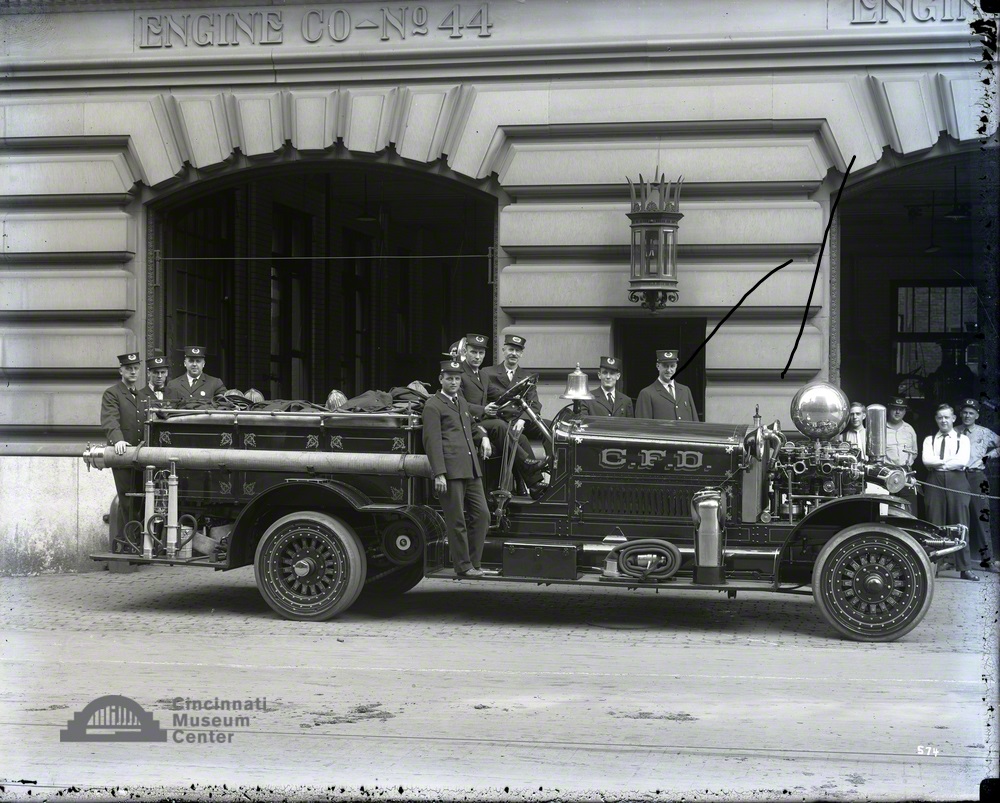

On November 11, Mayor Galvin declared the public tired of hearing about influenza and lifted the restrictions. Within a week cases among schoolchildren spiked and steadily increased throughout the month. By Thanksgiving more than 50% of cases were ages 3-14. Even then schools remained officially open although many, including the University of Cincinnati, closed due to a lack of attendance. It was at this point that children were banned from public places and parents whose children were not kept at home were charged with a misdemeanor. Besides children, firefighters in the city were exceptionally hard hit. Two companies had to be abandoned even as civilians stepped in to help. The firefighter cases overwhelmed General Hospital and overflow was redirected to the County Infirmary. Finally, on December 6 the restrictions were put back in place, but as the situation began to improve were again gradually lifted throughout the month.

When it was all said and done, it was reported that the 1918 death rate in Cincinnati was 25% higher than in the two preceding years and that 64% of deaths were people “in their prime.”

Sources: Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati Post. Photos are from the Cincinnati Museum Center Collection.

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children’s Museum.

| Adult (13+): | |

| Senior (60+): | |

| Child (3-12): | |

| Member Adult: | FREE |

| Member Child: | FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.