CMC Blog

Waltzing Matildasaurus!

By: Glenn Storrs, Withrow Farny Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology

OK, so there is no such thing as Matildasaurus, but there is a Muttaburrasaurus, an Early Cretaceous ornithopod dinosaur from northeastern Australia. Paleontology is not the world’s most lucrative profession, but it does have its advantages, often including the ability to travel for work. During this period of Covid-19 quarantine for so many of us, it seems like an opportune time to relive a paleo-adventure and share a little virtual travel Down Under.

The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology is an international professional organization that promotes research and education in the field of vertebrate paleontology, that branch of the science that includes the study of dinosaurs, such as Muttaburrasaurus, and other fossil vertebrates. The 79th annual SVP meeting, a gathering of paleontologists meant to share research and to network with colleagues was held in Brisbane, Australia, in October 2019. The 2020 edition is scheduled for Cincinnati, if the global pandemic does not intervene! In any case, the chance to travel to “Oz,” as Australia is sometimes affectionately known, was one that many northern hemisphere paleontologists just couldn’t miss.

Brisbane, the capital of the state of Queensland, is a thriving city on the east coast of the continent and a vibrant tourist destination. It is also home to the University of Queensland and the Queensland Museum, the SVP meeting co-hosts, and supports an active community of paleontologists. The Queensland Museum’s geoscience collection, based in the Brisbane suburb of Hendra, is the largest paleontological collection in Australia and one of the largest in the Southern Hemisphere. Vertebrate fossils were first recognized in Australia by Europeans in the 1830s, but active research on a wide variety of paleontology topics is currently underway by numerous homegrown professional and student researchers. The SVP meeting in Brisbane was only the third such meeting to be held outside of North America and the first in the Southern Hemisphere.

Downtown Brisbane and the Brisbane River from South Bank.

SVP Welcome Reception at the Queensland Museum featuring Muttaburrasaurus.

Skeleton of a platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) in the geoscience collection at Hendra.

The four-day meeting, as usual, was a great success with many interesting papers delivered, workshops and symposia given, committee meetings attended, and awards presented. The chance to discuss one’s own research and museum or teaching activities with peers is, in my view, always a highlight, especially when done over a nice pint of Aussie lager.

However, another of the great joys of SVP is the chance to travel on field trips to see important fossils and geology with local guides. “Local” may not be entirely accurate in this case, as one of the post-meeting trips went to Broome, in the Kimberley on the northwest coast, over 2500 miles away. Here we had a two-day look at the Cretaceous Broome Sandstone and its contained dinosaur tracks. This represents a diverse paleofauna but those of theropods (bipedal carnivores) and sauropods (giant herbivores) were particularly notable. Some of these, no doubt, gave rise to local stories passed down by the first peoples of Australia. Our gracious cultural guides welcomed us to their land and shared some of these fascinating stories.

The Indian Ocean coast north of Broome, Western Australia.

Dr. Steven Salisbury, University of Queensland, discusses theropod dinosaur tracks.

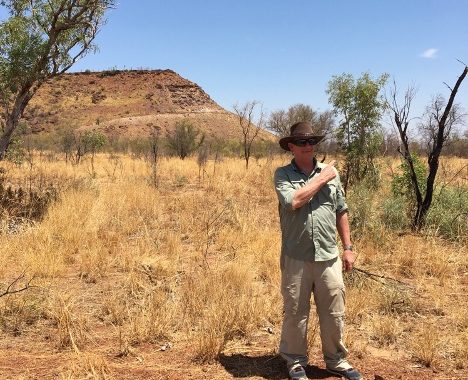

A 250 mile drive across the outback to Fitzroy Crossing allowed the intrepid group to visit the famous Gogo Formation inter-reef exposures of the Canning Basin. The interior of the “ancient great barrier reef” system can be seen in cross section in Geikie Gorge. First, however, we stopped briefly along the way at an outcrop of the Triassic Blina Shale, to see a quarry that has produced examples of the fossil brachyopid “amphibian,” Blinasaurus.

Prof. John Long of Flinders University with Blina Shale exposures behind.

The Gogo Formation is Devonian in age and world-renowned for its exquisite preservation of a three-dimensional fish and invertebrate fauna, occasionally with soft tissues preserved. Near Gogo Station, the group found and collected a rare fossil placoderm (extinct armoured fish), even though the dry Australian spring produced temperatures well into the 100o F range. Truly the trip of a lifetime for most of us who had only read about this famous place.

Devonian reef exposures and inter-reef facies near Gogo Station.

Dr Glenn Storrs, Cincinnati Museum Center, and Brent Breithaupt, US Bureau of Land Management, with Devonian reef limestones on the Fitzroy River in Geikie Gorge.

On the return drive to Broome, a visit to the Malcolm Douglas Crocodile Park was a must for any student of giant reptiles. Aside from birds, what could be closer to visiting with dinosaurs than Australia’s fearsome saltwater (or estuarine) crocodile (“saltie”)!

Saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) at Malcolm Douglas Crocodile Park.

Once again, back in Broome, it was time to relax before returning to Brisbane and then the long trip home to Cincinnati. Exhausting as the trip was, particularly when one factors in the time change and jet lag, SVP provides an opportunity for paleontologists to recharge, and to reignite the excitement and wonder that drove them to study the history of life and the distant past in the first place. We all hope that a Cincinnati meeting later this year will be able to do the same for our Australian and other international friends.

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children’s Museum.

| Adult (13+): | |

| Senior (60+): | |

| Child (3-12): | |

| Member Adult: | FREE |

| Member Child: | FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.