CMC Blog

Bottoms Up or Demon Drink? Cincinnati and the 18th Amendment

By: Katherine Gould, Curator, History Objects and Fine Art and Sarah Staples, Helen Steiner Rice Archivist

The Queen City has a long and complex relationship with intoxicating spirits, such as beer and wine. The business of making and selling adult beverages has deep roots in the city’s economy and social fabric. Davis Embree opened one of the city’s earliest breweries in 1811. [Image 1] Well-known vintner, real estate speculator and civic leader Nicholas Longworth planted vineyards that covered present-day Mount Adams, which produced his award-winning Catawba wine. [Image 2a-2d] And when German immigration increased in the 1830s and 1840s, these new citizens established multiple breweries that focused on the traditional German beer that was familiar to them, lager. [Image 3a-3b] At its peak in the 1800s, Cincinnati had 36 breweries and more than 300 vineyards within a twenty-mile radius of the city.

Of course, with production came consumption. In 1880, there were more than 1,800 saloons in Cincinnati, with 113 on Vine Street alone! The perception – and reality in many cases – was that husbands and fathers spent much of their free time and paychecks in the saloons. This situation, paired with an uptick in crime and expanding numbers of people who needed social welfare, led to activists pushing back against alcohol. [Image 4] As early as the 1840s, people formed religious societies to advocate for temperance: limiting or outlawing the drinking of alcohol.

In the mid-1800s, lawyer Samuel Fenton Cary was a leading voice for the Temperance Movement in Cincinnati, and later all of Ohio. While serving as the Grand Worthy Patriarch of the Ohio Sons of Temperance, this charismatic and fiery crusader also edited the Cincinnati-based Ohio Temperance Organ, where he published rants against liquor and drunkards. [Image 5]

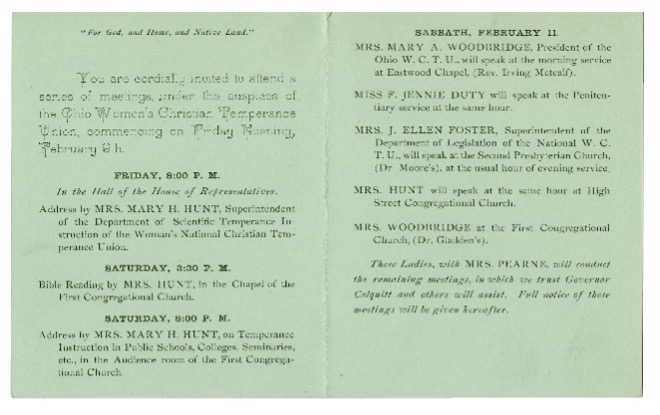

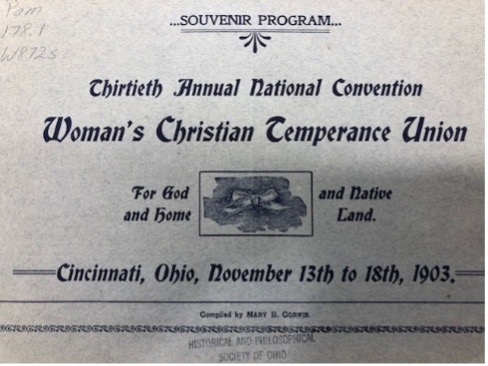

By the 1870s, many women’s temperance organizations led civic action against “Demon Rum” and “John Barley Corn.” Groups such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (founded in 1873 in Hillsboro, Ohio) positioned women as the “moral guardians” of the home. They worked aggressively for women and children, who suffered most when the men in their household drank away paychecks or became drunk and sometimes violent. [Image 6a-6b]

These grassroots organizations used many civic tactics to fight for their cause: marching through towns and praying outside saloons; delivering church lectures and fiery convention speeches; and lobbying elected officials. At a time when women couldn’t vote, the fight for temperance and prohibition gave women the ability and permission to operate in public spheres. Where they would normally be turned away, they could engage directly in political activity.

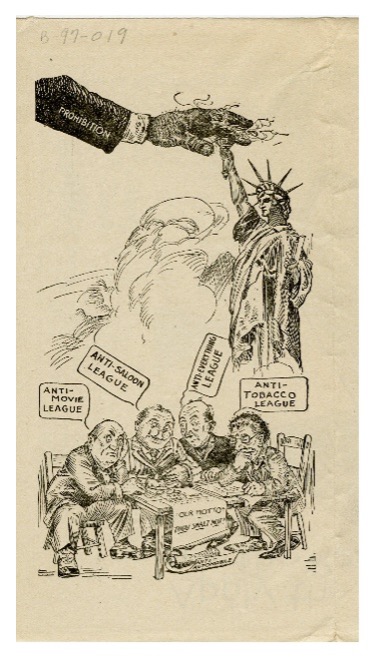

For some activists, social reform and temperance weren’t enough, and they wanted to ban the alcohol industry altogether. [Image 7] Founded 1893 in Oberlin, Ohio, the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) focused on a single political issue: prohibition. As pioneers in the use of “pressure politics,” the ASL quickly grew to become a powerful national organization. They fought to pass prohibition laws at the state level before focusing on a national amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

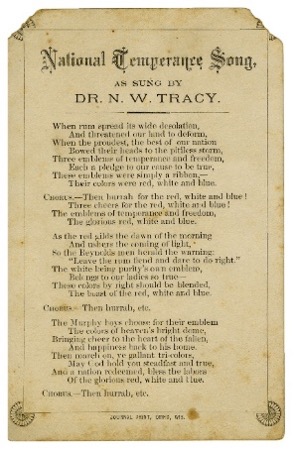

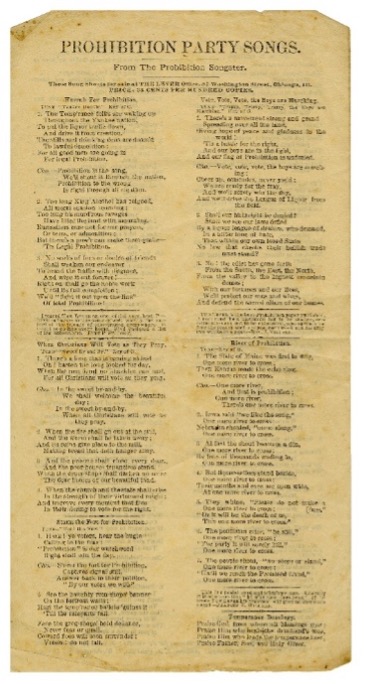

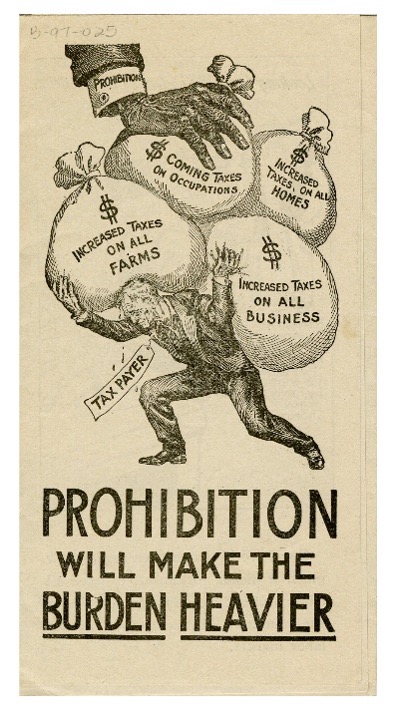

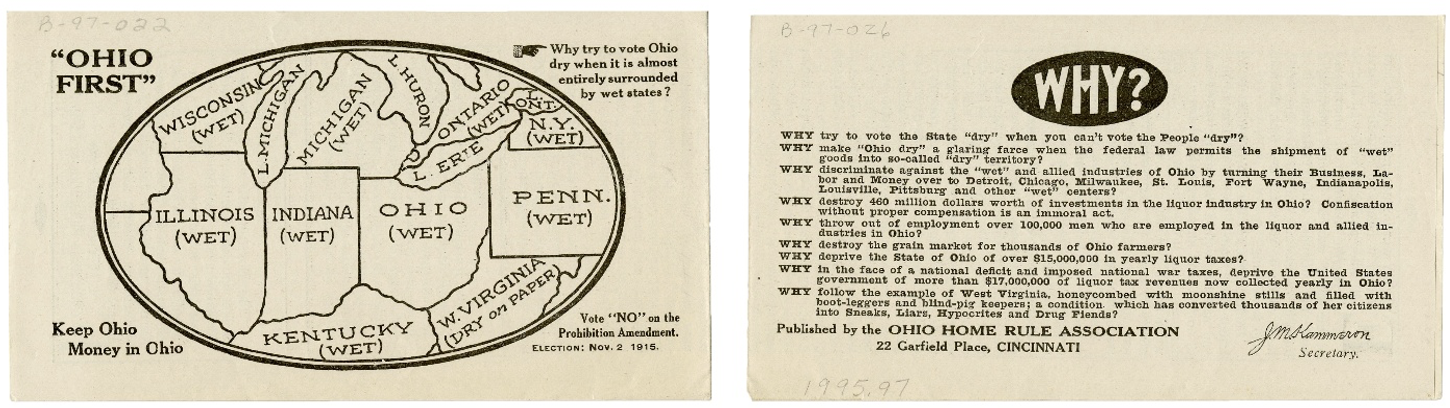

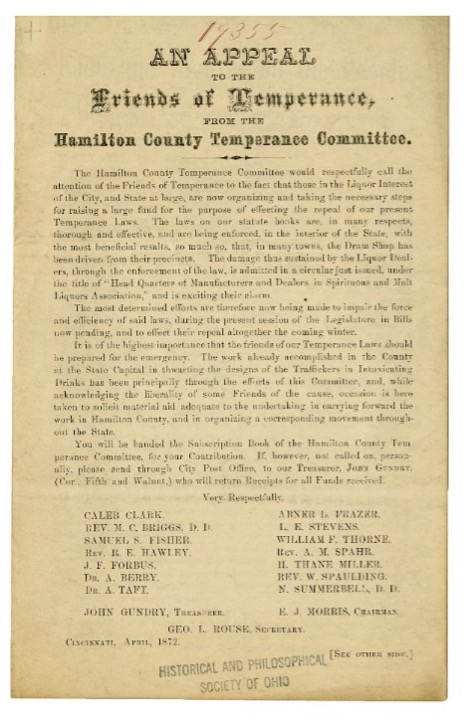

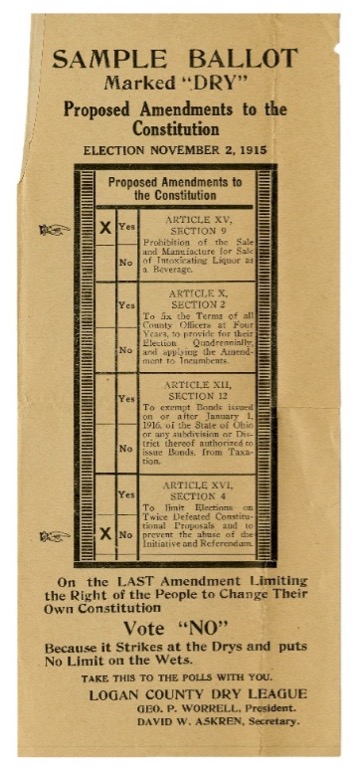

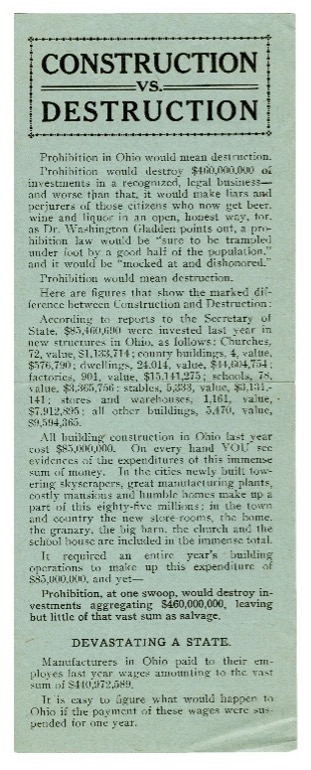

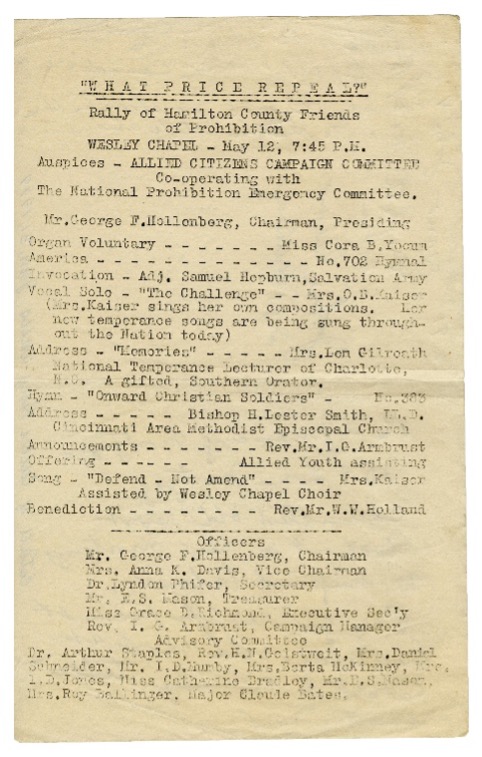

Groups both for and against prohibition published and distributed propaganda through pamphlets, newspapers, broadsides, songbooks, sheet music, illustrations and postcards. [Image 8a-8e] These documents give us insight into the arguments and civic tactics they used to convince voters of their cause. These archives also show that here in Ohio, a variety of state and local groups formed to fight for or against the issue: the Hamilton County Constitutional Prohibition Alliance, Hamilton County Temperance Committee, Hamilton County Friends of Prohibition, The Ohio Home Rule Association, Logan County Dry League and The Ohio Temperance Union, to name a few. [Image 9a-9f]

Eventually, the civic advocates for prohibition succeeded. Ohio passed a statewide prohibition amendment, outlawing alcohol and going “dry” in May 1919. Six months later, states ratified the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. This action meant that from 1920 until 1933, the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” was outlawed in the United States. The “noble crusade,” as it was often called, was the result of a century of grassroots organizing and coordinated political agitation at the local, state and national levels. [Image 10a-10b]

But the teetotalers’ victory was short-lived. Ultimately, the attempt to force social reform through legislation failed. The 18th Amendment created a number of unintended consequences, including a rise in bootlegging and organized crime, vast political corruption and increased drinking and the flagrant disregard for the law. All of these factors led to the eventual repeal of the Prohibition amendment in 1933.

But for Cincinnati, the damage was done. The impact of Prohibition on Cincinnati breweries, saloons and related industries was devastating, and nearly all of them went out of business. Some of the larger brewing firms, such as Christian Moerlein and John Hauck Brewing Co., tried to produce near-beer or soft drinks to survive Prohibition, but they failed to remain profitable and closed. Hudepohl Brewing Co. successfully survived Prohibition and became the only pre-Prohibition brewery to operate on a national scale. [Image 11]

The 18th Amendment couldn’t have passed – or been repealed – without coalitions of people working to make the U.S. “a more perfect union.” By understanding how our Constitution can change, we keep it a living document that adapts to new challenges that arise in our country’s history.

Image 1: Daniel Drake, Natural and Statistical View, or Picture of Cincinnati and the Miami Country, Illustrated by Maps, 1815. Map of Cincinnati showing a structure between Elm and Race Streets. (R.B. 917.714 D761, 1815, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 2a: Silver goblet awarded to Nicholas Longworth by the Ohio State Board of Agriculture for the Best Sparkling Catawba Wine, 1852. (2012.24.01, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 2b: N. Longworth wine bottle, ca. 1840. (2016.13.04.2, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 2c and 2d: Anderson, W., Longworth's Wine House, Cinti, OH, 1866. (PAM 634.8 A552, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 3a: Laggering tunnel cold storage, Cincinnati, n.d. (General Photograph files: Breweries, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 3b: Beer bottles from Cincinnati breweries, ca. 1890-1910s. (History Objects Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 4: “Eleven Years a Drunkard. The Life of Thomas Doner” temperance propaganda, 1878. (PAM178.1 D686, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 5: The Western Washingtonian, and Sons of Temperance Record, August 9, 1845, edited by Samuel F. Cary. (178.05 fW527w, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 6a: Invitation for the Ohio Women’s Christian Temperance Union meeting, ca.1870s. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 6b: Program from the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Convention held in Cincinnati, 1903. (PAM178.1 W8725, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 7: Program for the National Prohibition Convention held at Music Hall, Cincinnati, 1892. (PAM178.1 N277, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 8a: “National Temperance Song,” n.d. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 8b: “Prohibition Party Songs,” n.d. The Prohibition Party was founded in 1869 and has nominated a candidate in every presidential election since 1872. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 8c: “Prohibition Will Make the Burden Heavier,” anti-prohibition cartoon, n.d. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 8d: Anti-prohibition cartoon, n.d. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 8e: “Ohio First” anti-prohibition flyer, Ohio Home Rule Association, 1915. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 9a: An Appeal to the Friends of Temperance, from the Hamilton County Temperance Committee, 1872. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 9b: Constitutional Prohibition Amendment Alliance, Cincinnati, 1883. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 9c: Sample ballot for proposed Ohio state-wide prohibition constitutional amendment, Logan County Dry League, ca. 1915. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 9d: Temperance Opposed to Prohibition, The Ohio Temperance Union, ca. 1915. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 9e: Anti-Prohibition pamphlet, Ohio Home Rule Association, ca. 1915. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 9f: “What Price Repeal?” rally program, Hamilton County Friends of Prohibition, ca. 1933. (Temperance and Abstinence folder, Ephemera Collection, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 10a: Anticipating the ratification of the Prohibition amendment, Cornelius Hauck of Hauck Brewery applied for a patent for non-alcoholic beer in 1917. (Backlog: Hauck Collection, Sooty Acres, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Image 10b: Bruckmann Brewery’s "Malt Tonic" was made with less than 2 percent alcohol by volume (ABV) and was manufactured and sold for “Medicinal Purposes Only" during Prohibition. (2021.47.01, Cincinnati Museum Center).

Image 11: Gerke Brewing employees, n.d. (General Photograph files: Breweries, Cincinnati Museum Center)

Buy Tickets

Museum Admission includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children’s Museum.

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.