CMC Blog

Archaeological Evidence for the Presence of Dogs at the Hahn Site

By: Cincinnati Museum Center Archaeology Intern

At the Hahn Site, located near the border of Anderson Township and Newtown, Ohio, CMC archaeologists have unearthed a plethora of prehistoric Native American artifacts. Among the pottery, lithic tools and food byproducts lies evidence for the presence of domesticated dogs. While many dog bones have been recovered during CMC’s Hahn Site Archaeology Field School, other canine-related artifacts tell more of the story about domesticated dogs and Late Prehistoric village life in the Middle Ohio Valley. Below you will see three images showing that Fort Ancient people and dogs lived together in the lower Little Miami River Valley.

The first picture exhibits the proximal end (top) of a turkey femur. While the recovery of processed animal bones is not unusual, this particular bone shows evidence of carnivore gnawing and subsistence. Looking closely, small puncture marks from canine and carnassial (carnivore premolars) teeth are visible. Although Fort Ancient people subsisted primarily through maize agriculture, hunting and gathering was an important subsistence practice to supplement seasonal fluctuations in the availability of agricultural resources. In this case, they hunted or captured a wild turkey. After the animal was processed for protein and raw materials, it is assumed that the remains were discarded and scavenged by village dogs. Any remaining protein or marrow left on the discarded bones would have been targeted by village dogs as an important meal.

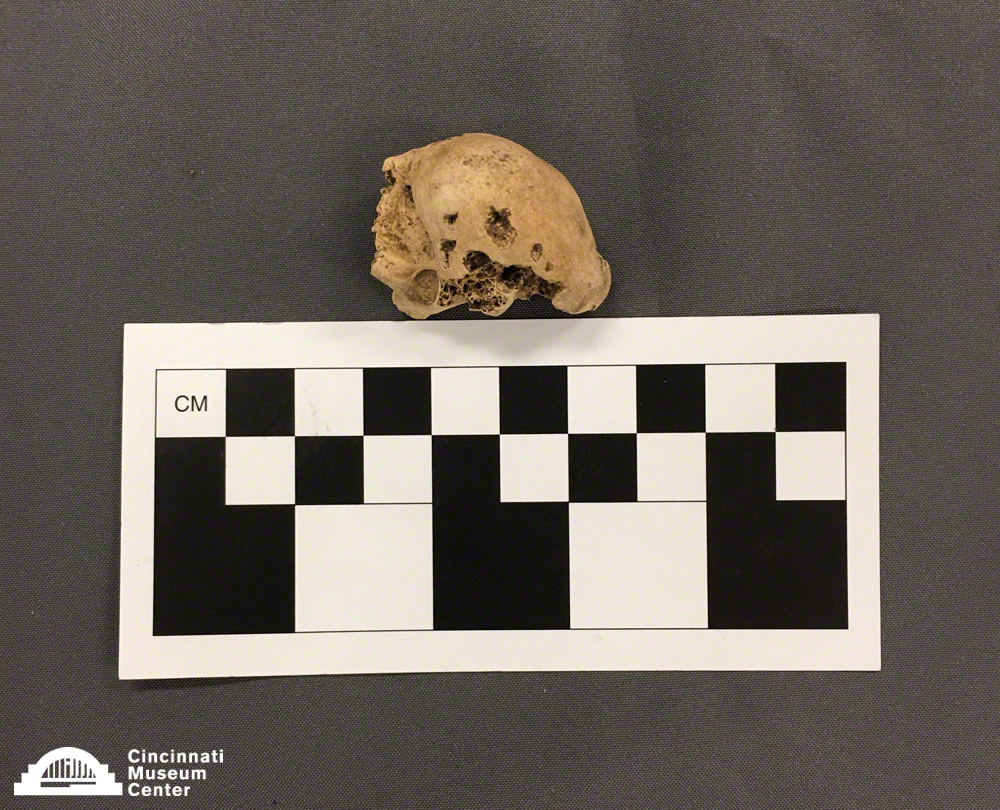

The next photo tells more of the story than meets the eye. On closer inspection, the surface of the bones show evidence of a formation process called pit and polish, which develops when stomach acids begin to break down bone that has been digested. Because it is very unlikely that humans or other wild animals consumed these bone fragments, it is probable that a village dog consumed them while scavenging everyday refuse. Following consumption, the bones passed through the canine’s digestive tract, resulting in the pitted and polished surfaces. At the Hahn Site, numerous bones with pitting and polishing have been recovered, suggesting that village dogs routinely ate refuse that developed from processing animals.

The last picture shows a dog canine that measures roughly 29 millimeters (1.14 inches) long and has a maximum width of 5 millimeters (0.2 inches). The canine has been drilled for suspension, suggesting that it most likely served a jewelry or ornamentation function. Because this canine was not completely developed (note the incomplete root), it had to have originated from a young dog. This drilled canine is also among many that have been recovered to date during CMC investigations at the site. The commonality of drilled canines affirms that dogs were an important part of life at the Hahn Site, and may even provide insight into village social organization, including the potential for dog clans.

We suspect that the above artifacts are associated with dogs, rather than other local carnivores, because of their size and location of discovery. They were recovered within the village, which was palisaded, from features such as storage pits, earth ovens and hearths. Their association with domestic proveniences indicates that these animals were probably not wild and instead lived in, or near, the village. The size of the puncture marks and drilled canine also shows that they had to have originated from smaller animals (Fort Ancient dogs were only about 30 lbs.) and not from larger carnivores such as bears, mountain lions, bobcats or wolves. Similarly, raccoons and opossums are probably too small to have left the puncture marks or to have consumed, digested and passed the pitted and polished bones. The discovery of a dog burial in 2011 also unequivocally documents the presence of dogs at the Hahn Site and comparison with modern reference collections that include domesticated dogs further support our interpretations.

Dogs were an integral part of Late Prehistoric village life and were important for hunting, alarm systems and as “beasts of burden.” They were an everyday part of Late Prehistoric village life and habitations with long occupation spans, like the Hahn Site, provide rare opportunities to analyze the role of domesticated dogs in the Ohio Valley prior to the arrival of Europeans. Unfortunately, other than size, archaeologists do not know what Fort Ancient dogs looked like. However, it’s safe to assume that they didn’t look like many of the special breeds that are available today, such as Pugs, Chihuahuas or Pomeranians because these are a relatively late development among modern breeders. Do you think Fort Ancient dogs could have looked like yours?

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children’s Museum.

| Adult (13+): | |

| Senior (60+): | |

| Child (3-12): | |

| Member Adult: | FREE |

| Member Child: | FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.