CMC Blog

The Cincinnati Arch

By: Cameron Schwalbach

Cincinnati and the surrounding region are known around the world for their abundant and well-preserved Ordovician-age fossils. The rocks beneath the city and its surrounding area preserve evidence of an ancient marine ecosystem that once inhabited this region nearly 450 million years ago. For nearly 200 years, paleontologists have used these fossils and the rocks in which they are preserved as a unique natural laboratory to examine important aspects of Earth’s history such as evolution, biotic invasion, climate change, sea level fluctuations, and plate tectonics during the Ordovician Period. So how is it that fossils from an ocean that was around nearly half-a-billion years ago can be found in the middle of the North American continent? The answer lies in the formation of the Cincinnati Arch.

Discovered by John Locke during his work with the First Geological Survey of Ohio in 1839, the Cincinnati Arch is a large geologic feature serendipitously centered on the city of Cincinnati. It is a broad structural uplift with the Illinois Basin to the west, the Michigan Basin to the northwest, and the Appalachian Basin to the east and southeast (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map showing regional tectonic features surrounding the Cincinnati Arch. Image taken from Bedrock Geology of Marion County by Nancy R. Hasenbueller and Walter A. Hasenmueller (igws.indiana.edu).

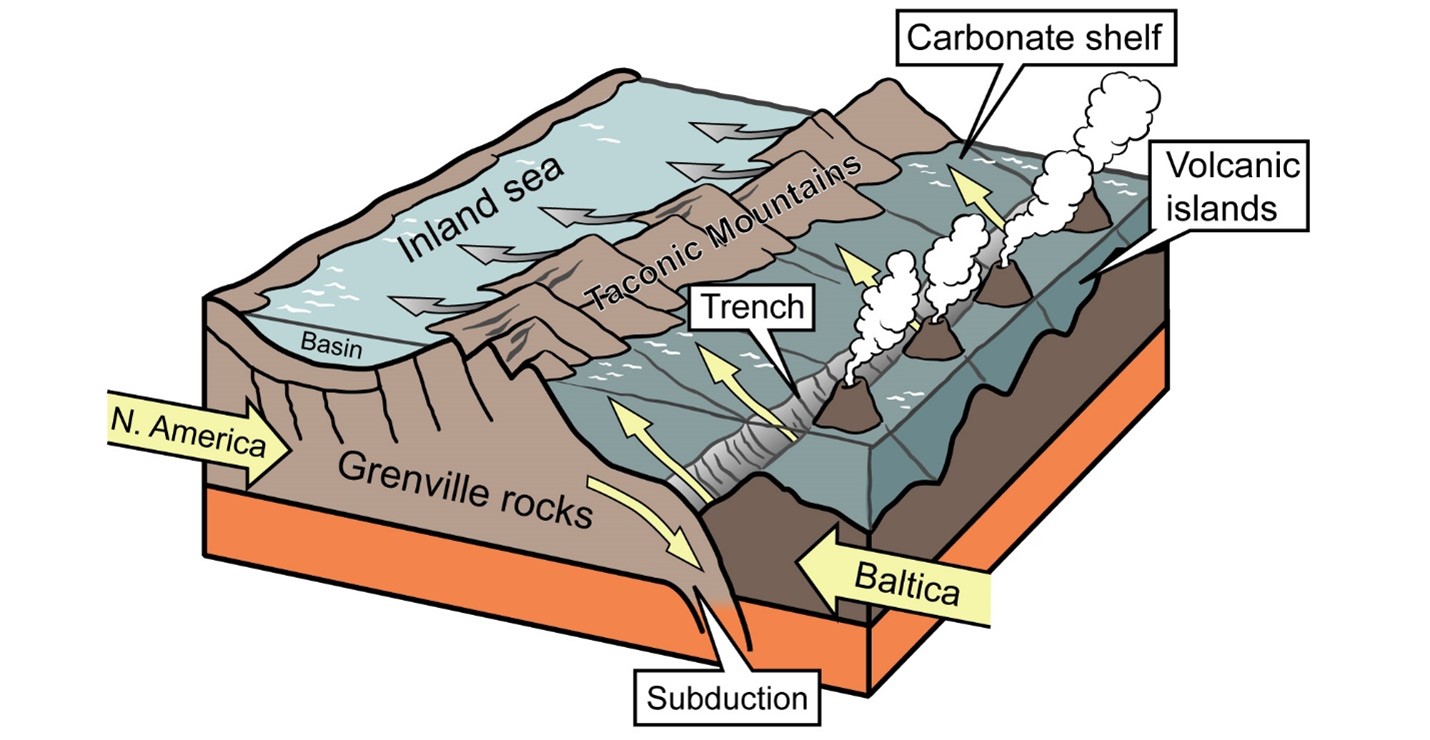

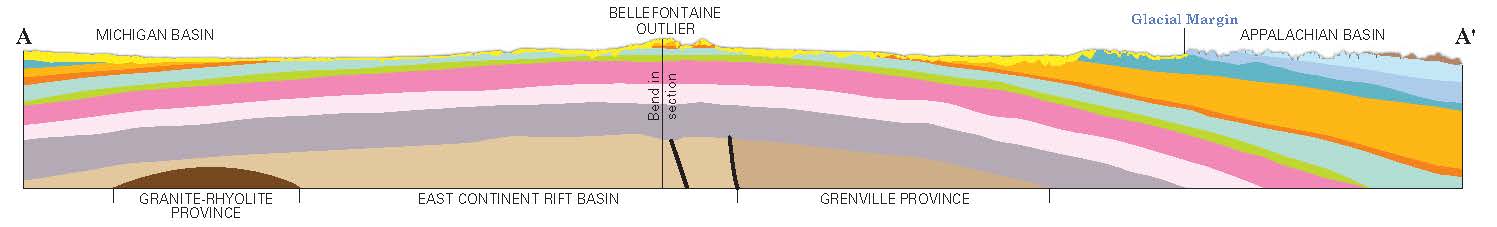

Features such as this form inland during mountain building events called orogenies, wherein enormous regions of rock are thrust together through the tectonic movements of crustal plates, piled up, and subsequently bent and folded as they are put under great pressure. As a mountain belt forms (in this case, the Taconic Mountains to the east), its immense weight pushes down the Earth’s crust beneath it, forming a basin (Figure 2). On the other side of this basin, the crust is bent upwards forming the opposite of a basin – an arch. Over millenia, the top of this arch is eroded away by rivers and glaciers, leaving the oldest rocks exposed at the center of the arch and the youngest rocks on the flanks (Figure 3). In the case of the Cincinnati Arch, the oldest exposed rocks date from the Ordovician Period and the youngest from the Permian Period.

Figure 2. Image showing the formation of the Taconic Mountain belt and the accompanying inland basin on the North American continent. The periphery of the Cincinnati Arch uplift can be seen on the left edge of the image. Image modified from original by J. Houghton first published in The Teacher-Friendly Guide to the Geology of the Northeastern U.S. by Jane Ansley (published by the Paleontological Research Institution).

Figure 3. Northwest to southeast transect across the state of Ohio showing subterranean bedrock. Note the shape of the Cincinnati Arch in cross-section. Ordovician rocks are shown in light and dark pink, with older rocks above and younger rocks below. Image taken from Ohio Division of Geological Survey, 2006, Bedrock geologic map of Ohio: Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geological Survey Map BG-1, generalized page-size version with text, 2 p., scale 1:2,000,000.

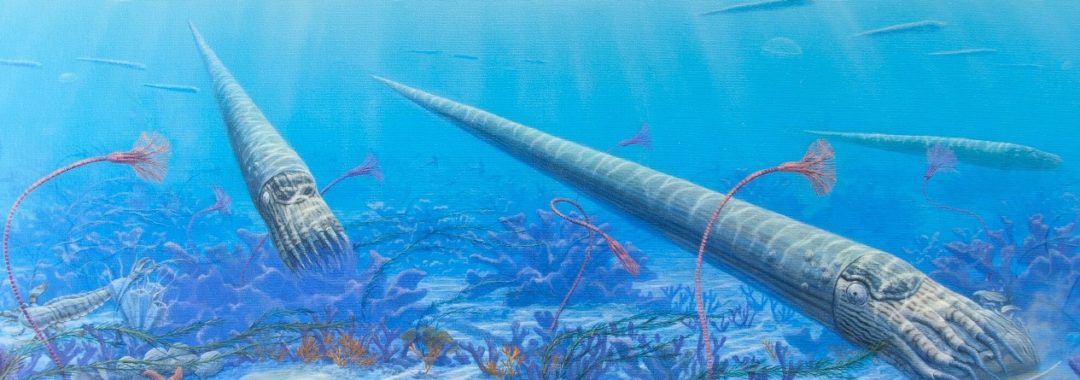

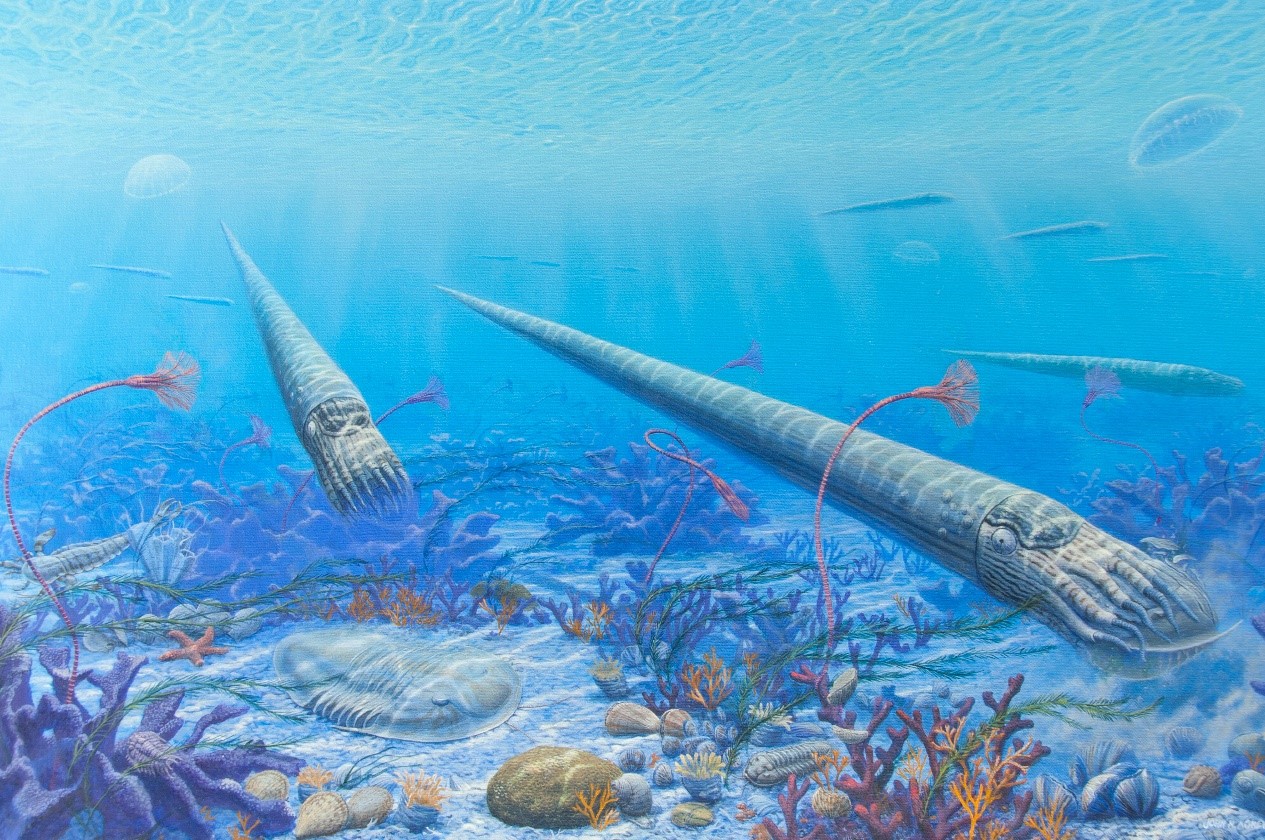

So that explains how the Cincinnati Arch was formed, but why are there fossils from an ocean in Cincinnati? To answer this, we must go back to when the Arch was first beginning to form. When the sediments that formed the Ordovician rocks beneath Cincinnati were deposited, the region was beneath a shallow subtropical sea in the southern hemisphere (Figure 4). This shallow marine ecosystem had environments that ranged from peritidal (around the shoreline) to deep offshore (about 150 feet deep), each with a unique composition of sediments and population of organisms. The Cincinnati area was subjected to frequent hurricanes that brought in muddy sediments shed from the building of the Taconic Mountains and interfingered them with carbonates produced by local organisms. The organisms living on or near the seafloor during these events were buried by the sediments, and if the conditions were right, went on to become fossils. The resulting layers of fossiliferous mudstone and limestone can be seen in roadcuts and creek outcrops throughout the region today. Stay tuned to learn more about the geology and paleontology of the Cincinnati region.

Figure 4. The Cincinnatian, oil on canvas, by John Agnew, 2007. This scene depicts life in the Cincinnati region as it may have appeared during the Ordovician Period, approximately 445 million years ago. Taxa depicted include medusa cnidarians, nautiloid cephalopods, eurypterids, crinoids, colonial corals, trilobites, bryozoans, brachiopods, rugose corals, bivalves, gastropods, edrioasteroids, conularids, and algae.

Museum Admission

Includes Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science and The Children’s Museum.

| Adult (13+): | |

| Senior (60+): | |

| Child (3-12): | |

| Member Adult: | FREE |

| Member Child: | FREE |

Members receive discounts!

Become a Member today to save on programs, exhibits and films throughout CMC.

Museum Hours

Open Thursday – Monday

10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed Tuesday and Wednesday

Closed Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day

Member’s-only early entry: Saturdays at 9 a.m.

Customer Service Hours:

Monday – Sunday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.